1. Introduction

Al-Cu alloys are traditional heat-treatable materials and are widely used in automobile and aircraft industries [1,2]. The strength increment of Al-Cu alloys during aging treatment is derived from the formation of nano-scale intermediate precipitates by the decomposition of a supersaturated solid solution [3]. The precipitation sequence, super saturated solid solution → Guinier-Preston (G.P.) I zone → θ” (G.P. II zone) → θ' → θ, is now generally accepted for Al-Cu alloys [4,5]. The plate-shaped θ′ (Al2Cu) precipitate is the primary strengthening phase among these precipitates [6]. Thus, except for the phase transformation in the precipitation sequence, the size, volume fraction and shape of θ′ precipitate will be changed with the aging process, which shows a prominent effect on the mechanical performances of the alloys. It should be noted that the changes in size, volume fraction and shape are closely related to the growth of θ′ precipitate, i.e. the solid-state phase transformation from Al-Cu solid solution (αAl, Fmm, a =0.404 nm) to θ' phase [7]. It is an important solid-state phase transformation which is out of the precipitation sequence.

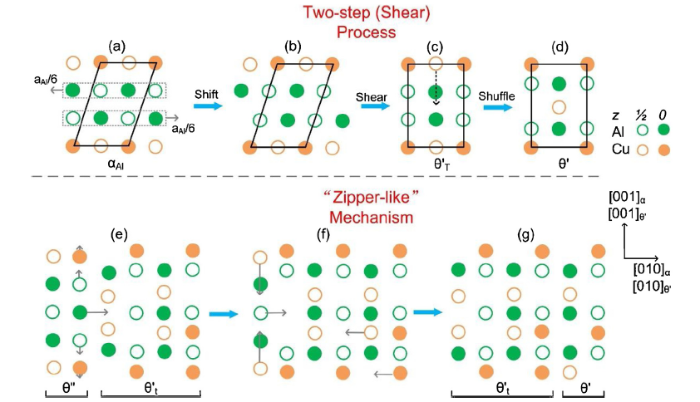

The θ' phase has a body-centered tetragonal crystal structure (space group I4/mmm, a = 0.404 nm, c = 0.580 nm) and an orientation relationship of (001)θ'//(001)α, [100]θ'//[100]α with the faced-centered Al matrix [[8], [9], [10]]. Considering different crystal lattices between phases, interfaces between θ' precipitate and the Al matrix can be divided into coherent and semicoherent conditions [[10], [11], [12]]. For the plate-like precipitate, its broad face is coherent since the misfit is small. However, the edge of the precipitate belongs to the semicoherent interface with a relatively large misfit, and the growth of θ' precipitate during aging is mainly carried out through the motion of this interface [11,13]. Thus, the aspect ratio and other characteristics of the plate-shaped precipitate depend significantly on the interfacial structure and growth mechanisms of θ' phase. Recently, some researchers focused on the relationship between the precipitation microstructures and mechanical performances of aging hardened alloys, in order to establish predictive models for the mechanical properties with high accuracy [1,[14], [15], [16]]. Other researchers focused on the thermodynamics and kinetics of precipitation by using computational simulations, such as the phase-field method, to study the evolution of precipitation structures in the alloys during aging [[3], [4], [5]]. However, these efforts should be carried out with a clear atomic-scaled growth mechanism of precipitates. Previous investigations about the growth of θ' phase or other precipitates were executed mainly by theoretical derivation based on indirect experimental evidences [11,13,[17], [18], [19], [20]]. Some striking growth mechanisms related to the motion of transformation disconnections have been studied, especially a well-known two-step process (or shear process) proposed by Dahmen and Westmacott based on the observed growth defects [[21], [22], [23]]. As shown in Fig. 1(a)-(c), the first step of the two-step process means that the middle two of the four layers of atoms shift a distance of aα/6 in opposite directions along {001} planes, followed by a homogeneous shear of the whole cell with an angle of arctan(1/3) to form an intermediate phase, defined as θ'T for simplicity in this study. The second step refers to the diffusion of Cu atoms, as illustrated by Fig. 1(c) and (d). In this step, Cu atoms shuffle from base-centered sites to body-centered position of θ'T cell, and therefore accomplish the αAl-to-θ' transformation to achieve the motion of interface. Although the observed transformation disconnections can support the shift and shear processes in this brilliant mechanism [11], very few experimental evidences can reflect the atomic diffusion accurately. Recently, some experimental images showing the intermediate structures in the αAl-to-θ' transformation have been obtained by atomic scale imaging to suggest some special mechanisms, such as the “zipperlike” mechanism [7,10]. This mechanism of transformation allows interfaces to move through a complex zipperlike action of a series of individual atomic movements, and the detailed process is illustrated by Fig. 1(e)-(g). However, the exploration of atomic diffusion in the well-accepted two-step process is still insufficient in experiments because it is hard to capture the intermediate structure on the phase interfaces.

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Schematics of the θ' precipitate growth through (a-d) the classical two-step process (or shear process) and (e-g) the “zipper-like” mechanism, respectively. Different colors represent different types of atoms. Gray arrows show the motion of atoms.

For this purpose, we conducted a detailed observation for the plate-shaped θ′ precipitates in an aged Al-Cu alloy using the atomic-scale high-angle annular dark-field scanning transmission electron microscopy (HAADF-STEM). The alloy was designed to form a single type of precipitates (θ' phase) via aging treatment based on our previous study [24]. Two novel interfacial structures have been observed, reflecting two unreported mechanisms of atomic diffusion of precipitate growth based on the well-known two-step process. One interfacial structure shows that Cu atoms can diffuse by an interstitialcy mechanism, which may be more efficient than the direct shuffle in the two-step process. In addition, a newfound intermediate structure enables Al atoms to act as diffusion atoms to form θ' phase, instead of Cu solute atoms in other reported structures [12,21]. The first-principle calculated results for the intermediate phase confirm that these transformations based atomic diffusion are energetically favored. These important mechanisms are foundations to understand and predict the evolution of precipitation microstructures. This work also stresses a phenomenon that local structural fluctuation of solid solution can induce structurally preferred diffusion of atoms during phase transformation process, which can also make a further development for diffusion theory.

2. Experimental and computational procedures

2.1. Sample preparation

An alloy with the composition of Al-3.5Cu (wt%) used in this work was cast from a pure Al bulk and an Al-50Cu (wt%) master alloy by using a medium frequency induction furnace. After homogenization annealing at 500 °C for 24 h, the ingot with 24 mm in thickness was hot rolled at 450 °C to an 8 mm thick sheet. Samples were solution treated at 520 °C for 1 h and then quenched to the room temperature in water. Then, isothermal aging was performed immediately at 200 °C for 48 h. Samples for TEM observations were prepared by mechanical thinning and then electropolished in a solution of 70 % methanol and 30 % nitric acid at 14 V and ‒30 °C.

2.2. TEM studies

The interfacial microstructure of θ' precipitates was characterized using a Thermo Fisher Titan cubed Themis G2 300 TEM equipped with a probe-forming Cs corrector operating at 300 kV. The TEM has a high resolution of 0.06 nm. The convergence angle for HAADF-STEM imaging was 25.6 mrad. The inner and outer collection angles were 52 and 200 mrad, respectively. Superimposing of 50 fast scan images recorded with the drift corrected frame integration (DCFI) technology were used to enhance the image contrast between atomic columns. Fast Fourier transform (FFT) filtering was carried out to remove the high-frequency noises of the raw atomic-scale HAADF-STEM images. Based on the Digital Micrograph software, the filter script with the default setting, written by Kilaas [25], was used in this process.

The HAADF-STEM image simulation was performed using QSTEM [26] according to the electron microscopic parameters. In this simulation, the thickness of the sample was properly assumed to be 10aα to make a good compromise between the accuracy and efficiency of the simulation. The slice thickness of 0.202 nm was chosen to cover single atomic layer. The value about the thermal diffusion scattering was set as 10. Besides, the source size of 0.1 nm was selected for the display of simulated images.

2.3. First-principles calculations

First-principle calculations were performed using Vienna ab initio Simulation Package (VASP) based on the density functional theory (DFT) [27,28]. The generalized gradient approximations (GGA) [29] and Projector augmented-wave (PAW) [30] potentials were adopted in this calculation. A k-point grid of 9 × 9 × 9 and an appropriate cut-off energy of 400 eV were chosen to achieve accurate energy differences. The structural parameters of each model were determined by the experimental data. All calculated structures were fully relaxed, including volume and atomic positions.

In this work, the formation enthalpies per atom of different phase during the transformation can be calculated from the Eq. (1):

where xAl = x/(x + y) and yCu = y/(x + y). E(AlxCuy), E(Al) and E(Cu) are the energies of the compound AlxCuy, the face-centered cubic aluminum and the face-centered cubic copper, respectively. The formation enthalpy of θ' phase has been set as the zero enthalpy, and the relative formation enthalpy of other phases can thus be obtained.

3. Results

3.1. The θ' phase and its semicoherent interfaces with the Al matrix

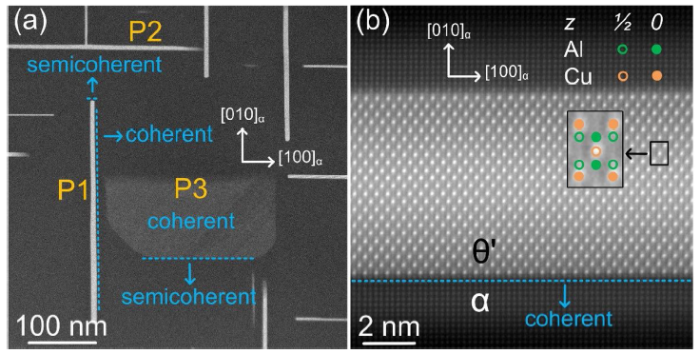

Fig. 2(a) shows a low-magnification HAADF-STEM image of the aged alloy. A high number density of precipitates can be observed in the image. As mentioned above, the orientation relationship between θ' phase and the Al matrix is (001)θ'//(001)α and [100]θ'//[100]α [12]. Two edge-on variants of θ' precipitates marked by P1 and P2, as well as the face-on variant marked by P3, are visible in Fig. 2(a). Semicoherent and coherent interfaces of edge-on and face-on variants are also marked by blue dashed lines. An atomic-scale image of the edge-on θ' precipitate is shown in Fig. 2(b). The brighter dots represent Cu atom columns that are parallel to the viewing direction. The Al atom columns are less visible than Cu, since the HAADF-STEM intensities of atomic columns are in proportion to Z1.7-1.9 [31]. Aluminum columns in the θ' phase appear vague due to their low Rutherford scattering cross section [31]. The crystal structure of θ' precipitate is described in the image. Besides, it can be seen clearly that the broad face of the precipitate is fully coherent with the Al matrix.

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

(a) Low magnification HAADF-STEM image showing three variants of θ' precipitates. (b) The atomic-scale HAADF-STEM image of an edge-on θ' precipitate and its coherent interface with the Al matrix. The inserted image shows the crystal structure of θ' phase. The viewing direction is parallel to [001] of the Al matrix.

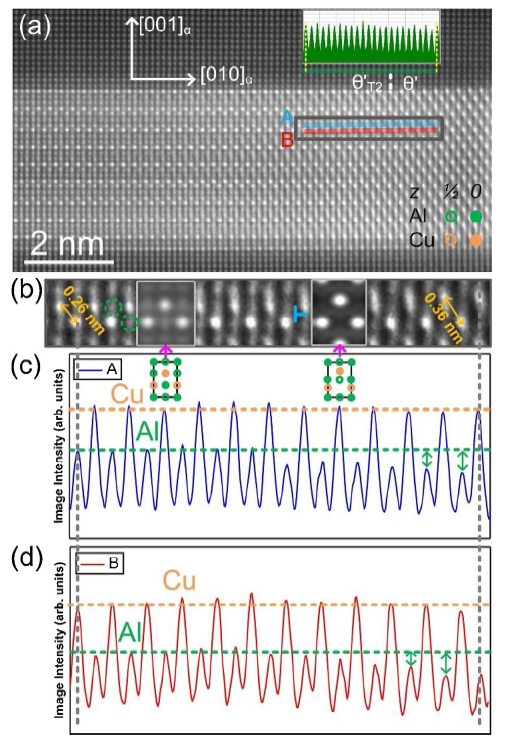

Fig. 3(a) displays a common semicoherent interface between the θ' precipitate phase and Al matrix viewed along <001>Al. While the Cu columns near the interface show a lower intensity because the precipitate is thinner here (along the viewing direction), and no other intermediate phases can be found on this boundary. Local misfit exists on this interface because of the difference in lattices between those two phases. This interfacial structure is stable, and it is the most common semicoherent interface in the TEM observation [7]. A different semicoherent interface containing a narrow part of θ" is shown in Fig. 3(b). As reported by Bourgeois et al. [10], this interface indicates a “zipperlike” mechanism of atomic movements in the lateral growth of θ' precipitate, and the process is shown in Fig. 1(f) and (g). This mechanism corresponds to αAl → θ" → θ' phase transformation, which is similar to the general precipitation sequence in Al-Cu alloys. In this growth mechanism, the front θ" phase acts as a source of Cu atoms to support the formation of the new θ' units. Furthermore, the atoms in the transitional zone (θ't) between the θ" and θ' phases show a zipperlike action to accomplish the complex phase transformation. In addition, some additional bright dots appear on the coherent interface between the θ' phase and the Al matrix, as marked by orange arrows in Fig. 3(b). These dots indicate that the interstitial positions on the coherent interface are occupied by additional Cu atoms. However, the interface related to the two-step process (or shear process) was not observed.

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

Atomic-scale HAADF-STEM images showing (a) the common and (b) a different semicoherent interface between θ' precipitate and the Al matrix. The interfacial structure in (b) reflects the “zipperlike” mechanism during the growth of θ' precipitate. Interstitial Cu atoms on the coherent interface are marked by orange arrows.

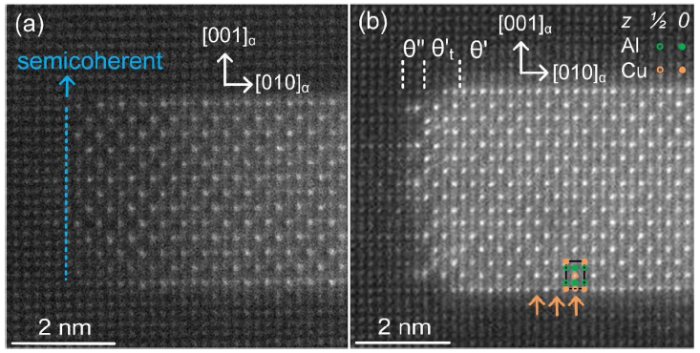

3.2. The interfacial structure based on interstitialcy mechanism of atomic diffusion

The HAADF-STEM image of a semicoherent interfacial structure on an edge-on precipitate is shown in Fig. 4(a) and viewed along [100]α. This structure is constituted by three parts, as marked by two dashed lines in the image. Clearly, the rightmost section shows the θ' phase, and the leftmost section is a combination of the Al matrix and the intermediate phase θ'T1. These structures nicely match the two-step process illustrated in Fig. 1 [23]. The θ'T1 phase has the same structure to θ'T phase, but it is named as θ'T1 to distinguish the intermediate phases in other interfaces. What’s more, a transition structure over a distance of about 2 nm, was found between θ'T1 and θ' phases and defined as θ'P1 phase. The θ'P1 phase has a similar structure to θ'T1 but contains an additional atom at the body-centered position of the cell. The transition area between θ'P1 and θ' is magnified in Fig. 4(b). The intensity contrast between atomic columns on A and B planes, as measured from the experimental HAADF-STEM image in Fig. 4(a), is shown in Fig. 4(c) by blue and red profiles, respectively. The structure of θ'P1 phase and corresponding diffusion process can be derived from the image. Firstly, as marked by green arrows in Fig. 4(b), there is an additional layer of atoms with lower intensity between two Al atom layers in θ'P1 phase compared to θ'T1 phase. Secondly, adjacent atom columns in A or B layer do not have a strong and ordered fluctuation in contrast, which indicates that the additional layer of atoms is only constituted by Al atoms and exist before the formation of θ' phase. Thus, for the θ'P1 phase existed before diffusion, higher intensities on A layer and lower intensities on B layer represent Cu and Al atomic columns, respectively. The HAADF-STEM image simulations and atom models for θ'P1 and θ' phases based on corresponding models in the Discussion section are overlaid on the appropriate positions in Fig. 4(b) and (c). With the image closing to θ' phase, the intensity of each layer increases with the thickness of the precipitate. What’s more, strong and ordered fluctuation of intensities between adjacent atomic columns appears simultaneously on A and B layers, indicating atomic diffusion between A and B layers during the transformation. The diffusion shows an interstitialcy mechanism through the intermediate phase θ'P1. The interstitial Cu atoms in θ'P1 phase shuffle to the center of the cell to replace the body-centered Al atoms and to form θ' phase, according to the intensity profiles marked by red and blue arrows in Fig. 4(c). The shuffle of Cu atoms is marked by orange arrows in Fig. 4(b). This unique interfacial structure reflects an important lateral growth mechanism of θ' precipitates.

Fig. 4.

Fig. 4.

(a) The atomic-scale HAADF-STEM image of a semicoherent interface on the edge of a θ' precipitate viewed along [100]α and (b) the crucial diffusion region obtained from the selected area in (a). Additional Al atoms and interstitial Cu atoms were marked by green arrows and orange circles, respectively. Simulated images for θ'P1 and θ' cell are overlaid in the image. (c) Intensity profiles of A and B planes marked in (a). The blue and red profiles represent the column intensity variations on A and B planes, respectively. The fluctuation of intensity reflects the atomic diffusion.

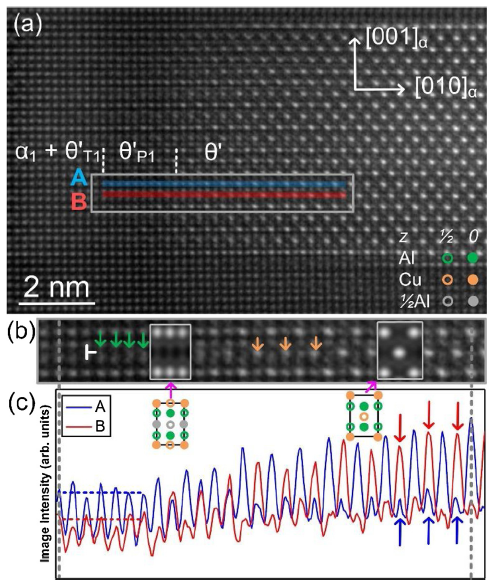

3.3. The interfacial structure based on direct diffusion of Al atoms

Fig. 5(a) shows the HAADF-STEM image of another semicoherent interfacial structure of the θ' precipitate. The intermediate phase θ'T2 on this interface is different from the above mentioned θ'T and/or θ'T1 phases. The θ'T2 can be formed from a solid solution α2 by a similar transformation process as mentioned above, i.e. shift and shear. The selected diffusion area in Fig. 5(a) was magnified in Fig. 5(b). The θ'T2-to-θ' transformation occurred from left to right in the image. Simulated images and atom models for θ'T2 and θ' phases were overlaid on the appropriate positions in Fig. 5(b) and (c), respectively. These simulated images match the experimental HAADF-STEM images perfectly. The intensities of atomic columns were measured for A layer, B layer and the matrix in Fig. 5(a). The inserted image in Fig. 5(a) shows the intensity of matrix. The same intensity of the same type of atomic column indicates that the effect of HAADF-STEM sample’s thickness on the intensity can be neglected in this area. The profiles of A and B layers in the experimental image are shown in Fig. 5(c) and (d), respectively. In the intensity profiles, Cu columns show a higher intensity than Al columns because of the Z-contrast. The intensity of Cu columns remains almost unchanged during the θ'T2-to-θ' transformation. However, the intensities of the Al columns on A and B layers reduce (from left to right) obviously because of the decrease in number of atoms in the columns. In addition, the image shows that the distance between A and B layers increases from 0.26 nm to 0.36 nm, with the formation of a new layer of Al atoms during the transformation. Thus, the formation of θ' phase on this interface relies on the diffusion of Al atoms from A and B planes, as marked by green circles in Fig. 5(b), into a new atomic layer. This unique interfacial structure reflects another important lateral growth mechanism of θ' precipitates. Although extensive experiments have been conducted in our study, only a few interfaces with these transitional phases have been observed. Thus, there is a lot of randomness to count and compare the frequency of different mechanisms.

Fig. 5.

Fig. 5.

(a) The atomic-scale HAADF-STEM image of a semicoherent interface on an edge-on θ' precipitate viewed along [100]α. The inserted image shows the intensity variation of the selected layer in the matrix. (b) The selected area in (a) showing the important transition region. Simulated images for θ'T2 and θ' cell are overlaid in the image. Some Al atoms are marked by green circles. (c, d) Intensity profiles of A and B planes, with the different intensities representing different atomic columns. The significant reduction of intensity was marked by the green arrows.

In order to determine the structural damage caused by electron beam during imaging, we have compared the HAADF-STEM images of these two newly interfaces before and after the DCFI imaging (see Supplementary Materials Fig. S1). It is found that the damage caused by electron beam during the DCFI imaging can be neglected in this study. In addition, Wenner et al. reported that the damage mainly occurs in the superstructure θ'D formed by adding Zn element in Al-Cu alloys, and the damage rarely occurs in the θ' phase [32]. Besides, the Nano-beam diffraction (NBD) may be able to provide more evidences for these mechanisms. However, the tiny transitional structures (especially the area related to the diffusion process) are still hard to locate accurately during the NBD process. On the other hand, extra NBD process may increase the chance of electron beam damage. Thus, HAADF-STEM imaging should be more suitable and effective in this case.

4. Discussion

During the aging treatment of Al-Cu alloys, the structure of precipitates will transform following the precipitation sequence. The θ' phase will form via consuming previous θ" phase at the early aging stage. However, the growth of θ' precipitates from Al-Cu solid solution is the dominating way to form θ' phase in the alloy with long-time aging, which is independent of the precipitation sequence. In order to facilitate the study of direct growth mechanism, an expected Al-Cu alloy only containing θ' precipitate was designed via long time aging, based on our previous study [24].

In aged Al-Cu alloys containing plate-like θ' precipitates, there are two different interfaces between the θ' phase and the Al matrix, i.e. the coherent and semicoherent interfaces. During aging treatments, thickening of θ' precipitates is intimately linked with the motion of coherent interfaces. Some interstitial sites on the coherent interfaces can be filled by Cu atoms, as shown by the orange arrows in Fig. 3(b). It is reported that this interstitial configuration is stable in energy and the additional Cu atoms can participate the thickening process of the θ' precipitate [7].

However, the lateral growth of θ' precipitate is mainly associated with the motion of semicoherent interfaces. Compared to the thickening process on coherent interfaces, the lateral growth is a more important process for the θ' precipitate in Al-Cu alloys under aging treatments, which could be observed from the plate-like morphologies of precipitates. This growth process depends on many factors, such as aging temperature and the local solute concentration. The phase transformation with respect to the lateral precipitate growth includes thermal activation process [10]. Thus, the growth of the precipitates cannot occur continuously because of the thermal activation barriers, which can explain why the interfaces containing the transition structure or other related intermediate phases were rarely observed. During aging, the precipitate growth strongly depends on various precursor phases, which are formed by individual atomic movements. The structural difference among different precursor phases in these growth mechanisms (including the new findings in this work and the reported zipperlike mechanism [10]) can generate different transition patterns. At the high aging temperature (i.e. 200 °C in this work), local structural fluctuation plays a prominent role for nucleation of the precursor phase, so as to affecting the growth mechanism of precipitates. Precipitation structures of the alloys depend strongly on the process of phase transformation. Different growth mechanisms of precipitates are associated with different activation energies, which will influence the kinetics of precipitation. Thus, growth mechanisms are crucial for controlling the performance of age-hardened alloys. For better understanding the effect of local structural fluctuation on the growth mechanisms of θ' phase, the detailed transition process corresponding to the interfaces in Figs. 4(a) and 5 (a) should be discussed on structural and energetic aspects at first.

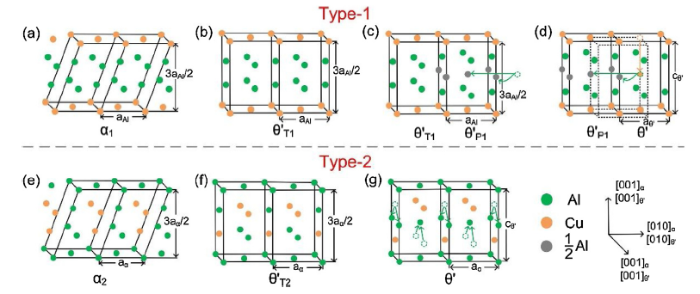

4.1. The lateral growth based on interstitialcy mechanism of atomic diffusion

The interstitialcy mechanism of atomic diffusion and the whole α1-to-θ' transformation process of the semicoherent interface in Fig. 4(a), defined as the type-1 transformation, are illustrated step by step in Fig. 6(a)-(d). According to the two-step process as mentioned above, the α1-to-θ'T1 transformation is shown from Fig. 6(a) and (b). According to the HAADF-STEM image of the first interface in Fig. 4, the θ'P1 phase contains additional Al atoms compared to the front θ'T1 phase. The position occupied by these extra Al atoms should be body-centered positions, which are large enough to accommodate an additional Al atom. It should be noted that the position of long edge center equals to the body center position of θ'T1 cell in crystallography, so that both of the two positions can be occupied by Al atoms, as shown by green arrows in Fig. 4(b). However, the Al atoms in edge center should diffuse to the body centered position to take part in the interstitialcy mechanism under the restrict of the strain field of the Cu layers in surrounding θ' phase. Thus, the diffusion process from Fig. 6(c) and (d) can be summarized as two steps. Firstly, the Cu atoms in θ'P1 phase shuffle from the base center position to the body center position to form a new unit cell of θ' phase. Secondly, the previous Al atoms on the body-centered position of θ'P1 phase diffuse to the adjacent θ'T1 cell, therefore to form a new θ'P1 from θ'T1 for continuing the transformation process. Considering the conservation of atoms, each unit cell of θ'P1 phase contains an additional Al atom, which is allocated to two potential positions and can be reflected by the lower contrast of atom columns in Fig. 4(b) than other Al columns. Besides, more positions occupied by atoms in θ'P1 phase will introduce a larger distortion. For example, the θ'P1 phase will have the similar structure to θ" phase, if all these positions are filled by atoms, but the large size of θ" lattice (cθ" =0.768 nm) does not have a good accommodation with θ' phase (cθ' =0.580 nm). For these reasons, the model of θ'P1 in Fig. 6(c) is reasonable. According to these models, simulated HAADF-STEM images for θ'P1 and θ' phases are overlaid on the appropriate positions in Fig. 4(b), verifying the accuracy of these crystal structures. The small difference in contrast of Cu columns between experimental and simulated images of θ'P1 phase is attributed to the θ'P1 phase being overlaid by Al matrix in experiments. In addition, it should be noted that these transitional structures were not disguises caused by the simple overlap of the θ' phase and the Al matrix, since the distance between two adjacent atomic columns on B atomic player is about 0.404 nm rather than 0.202 nm in the θ' phase. The simple overlap of θ' phase and Al matrix is schematically shown in Fig. S2. Fig. 3(a) represents a case of the simple overlap, which shows a different structure. Because atoms in this study is equal in size, diffusion can occur by this interstitialcy mechanism, which results in smaller distortion than direct diffusion [33,34]. In the θ′P1 phase, Al atoms on the body centered position will push the surrounded Al atoms. The following diffusion of base centered Cu atoms will introduce a smaller displacement of the Al atoms, compared to the direct diffusion, so it will occur relatively easier. Thus, the interstitialcy mechanism can reduce the thermal activation barrier during the transformation, and the essence of this transformation is still from θ'T1 to θ' phase. The intermediate phase θ'P1 acts as a catalyst to make the α1-to-θ' transformation more efficient than the direct shuffle in the two-step process. This interface contains a dislocation, as marked by the white notation in Fig. 4(b), with the Burgers vector of (aAl/2)[001] to accommodate the difference in lattice parameters between different phases. During the growth process, the dislocation will climb toward the negative direction by the diffusion of the Al atoms from the neighbor layer.

Fig. 6.

Fig. 6.

Schematics of the α1-to-θ' transformation in (a-d) for

4.2. The lateral growth based on direct diffusion of Al atoms

The second interfacial structure in Fig. 5(a) reflects another interesting growth mechanism based on the two-step process. Details of the whole α2-to-θ' transformation, defined as the Type-2 transformation, and the unique diffusion mechanism are illustrated in Fig. 6(e)-(g). According to a similar process in the two-step process, the θ'T2 phase can be generated from α2 phase. As an important intermediate phase, the θ'T2 phase shows a zigzag arrangement of Cu atoms in this transformation. The schematic diagram in Fig. 6(f) and (g) represents the diffusion zones in Fig. 5(b). The Al atoms in the middle two layers will diffuse to the nearest body or edge centered positions in the unit cell to form a new layer of Al atoms. Finally, the distance between the two layers of Cu atoms is enlarged and the θ' phase is formed. This mechanism involves the movement of a dislocation, as marked by the blue notation in Fig. 5(b), with the Burgers vector of (aAl/2)[001]. During the growth process, the dislocation will climb toward the negative direction by the diffusion of the Al atoms from the neighbor atomic layer.

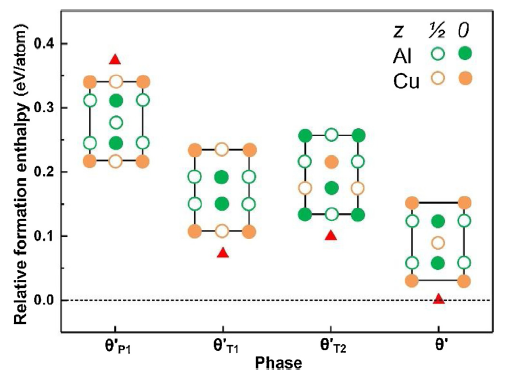

4.3. First-principle calculations

To check whether the transformations, especially in the diffusion process, are energetically favored, first-principle calculations were performed for θ'P1, θ'T1, θ'T2 and θ' phases. The results are represented by the red triangle and the crystal structure for each phase are shown in Fig. 7. The calculated formation enthalpy reflects the stability of each phase. The formation enthalpy of θ′ phase calculated in this work is ‒0.1773 eV per atom, which shows a good agreement with the value ‒0.18 eV from the reference [35]. In Fig. 7, the formation enthalpy of θ' phase is set as the zero enthalpy for clear comparison. It should be noted that the intermediate θ'P1 phase in the transformation is the variant with body-centered Al atoms rather than edge-centered Al atoms. Thus, the variant with body-centered Al atoms was used as the calculated model for θ'P1 phase. Besides, the θ'P1 phase, like a catalyst, is conservative through the transformation, so the essence of the first transformation as mentioned above is from θ'T1 to θ' phase. The intermediate θ'P1, θ'T1 and θ'T2 phases have higher formation enthalpy than θ' phase. Thus, it can be confirmed that the transformation from intermediate phases θ'T1 or θ'T2 to θ' phase is energetically favored, and the θ'T1 and θ'T2 phases can still exist as metastable structures during the phase transformation.

Fig. 7.

Fig. 7.

The relative formation enthalpy of the θ'P1, θ'T1, and θ'T2 phases represented by the red triangle and the crystal structure for each phase viewed along [100]. The formation enthalpy of θ' phase was set as the zero enthalpy for clear comparison.

4.4. The growth of θ' precipitates during aging

For Al-Cu alloys with a long aging period (e.g. aging at 200 °C for 48 h in this work), the growth of θ' precipitates is an important solid-states phase transformation during aging treatment. Understanding the growth mechanism is necessary for investigating the thermodynamics and growth kinetics of the plate-shaped θ' precipitate. The observation of interfacial structures demonstrates that the growth of θ' precipitates is subjected to a combination of several major mechanisms under this aging condition. Except for the zipperlike mechanism reported by Bourgeois et al. [7,10], two new mechanisms based on the theoretical two-step process were observed in this work using atomic-scaled imaging.

For the first mechanism observed in this work, the corresponding HAADF-STEM image in Fig. 4 clearly indicates an interstitialcy mechanism for atomic diffusion. In this process, the shuffle of Cu atoms in θ'P1 phase is accompanied by the diffusion of additional Al atoms which occupy the body-centered sites. This interstitialcy diffusion has a smaller distortion than the direct diffusion in the Al-Cu system. The decreased thermal activation barrier can make the whole phase transformation more efficient. For the second mechanism observed in this work, the atomic-scaled image in Fig. 5 shows a special intermediate structure containing a zigzag arrangement of Cu atoms, i.e. the θ'T2 phase. Only Al atoms participate in the diffusion process during the whole precipitate growth.

The diversity of growth mechanism or atomic diffusion is attributed to the local structure fluctuation. In these diffusional transformations, including the zipperlike process, the adopted diffusion mechanisms show a strong connection with the crystal structure of intermediate phase formed on the semicoherent interface. More exactly, atomic diffusions depend on several critical factors such as solute atoms (including type and concentration) and temperature. It is well known that the temperature or the concentration of solute atoms can change diffusion coefficient, therefore promote or restrain the phase transformation or precipitate growth [36,37]. However, fluctuation of local structure in solid solution generated by thermal activation can also change the diffusional transformation, which can be clarified by the observation in this work. The local structure fluctuation relies on thermodynamics and kinetics of solute atomic diffusion in the matrix. In the Al-Cu system, the high temperature aging (e.g. 200 °C) can provide more kinetically favored possibilities for some extra solid solutions (e.g. α1 and α2 in this work), although they may not be energetically preferred. These solid solutions will evolve into different intermediate phases with aging. Different atomic diffusion mechanisms are not only structurally preferred but also energetically favored for the intermediate phases to accomplish the subsequent diffusional transformation. Thus, the local structure fluctuation in the alloy has a significant effect on controlling the growth of θ' precipitates. Finding a way to modify the local structure around interfaces may become an efficient and desirable way to control the precipitation microstructure of age hardening alloys, and ultimately to promote their mechanical or other performances. Except for aging temperature, the transformation mechanism will also change during the aging treatment. This is due to the fact that the concentration of Cu in solid solution will decrease with aging treatment. The diffusion coefficient of atoms in the solid solution can also be changed with the concentration. Finally, the thermodynamics and kinetics of precipitates growth will thus be affected. It can be concluded that, in all the mentioned growth mechanisms, the two-step mechanism is more available at low aging temperature, since it is more favored in thermodynamics at low temperature. The “zipperlike” mechanism is better suited at the early stage of aging, in which θ" phases are enriched at the tip of the precipitates. However, two new mechanisms found in this work is more competitive at the high concentration of solutes. However, it is hard to identify these factors in detail right now. More experiments and simulations are needed on this direction.

Our study provides valuable experimental evidences for the θ' precipitate growth during aging treatment. Two striking and alternative diffusion mechanisms have been proposed to perfect the two-step process theory on the growth of plate-like precipitates. These atomic diffusion based mechanisms are crucial for exploring the thermodynamics and kinetics of the solid-state phase transformation in Al-Cu alloys or other heat-treatable alloys during aging. Different growth mechanisms will introduce varied thermal activation barriers for phase transformation, and finally affect the growth rate of θ' precipitate. Thus, the atomic-scaled understanding in growth mechanism of θ' precipitates is the foundation to accurately simulate and predict the precipitate growth and shape.

5. Conclusion

A comprehensive observation of the precipitation microstructure, especially the interface between αAl and θ' phase, in an aged Al-Cu alloy has been performed using the atomic-scaled imaging. The atomic-scale characterization has demonstrated that the growth of θ' precipitates is subjected to a combination of several major mechanisms. Except for the zipperlike mechanism, two alternative diffusion mechanisms of atoms were observed based on the well-known two-step process (or shear process). One corresponds to an interstitialcy mechanism by additional Al atoms. Another is achieved via direct diffusion of Al atoms other than the solute Cu atoms. The DFT calculations of intermediate phases and θ' phase confirm that these diffusional transformations are energetically favored. This work provides a comprehensive introduction of the lateral growth mechanisms of the θ' precipitate in aged Al-Cu alloys.

Acknowledgements

This work was financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 51531009 and 51820105001). We would like to thank Professor James M. Howe at the University of Virginia for valuable comments.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary material related to this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmst.2020.05.046.

Reference

DOI

URL

PMID

[Cited within: 2]

We demonstrate how three

DOI

URL

PMID

[Cited within: 7]

Atomic-scale imaging and first-principles modeling are applied to the heterophase interface between the Al-Cu solid solution (alphaCu) and theta' (Al2Cu) phases. Contrary to recent studies, our observations reveal a diffuse interface of complex but well-defined structure that enables the progression from alphaCu to theta' over a distance of approximately 1 nm. We demonstrate that, surprisingly, the observed interfacial structure is not preferred on energetic grounds. Rather, the excess in interfacial energy is compensated by efficient atomic-scale kinetics of the alphaCu-->theta' phase transformation.

AbstractSurface relief angles observed for diffusional plate-like products suggest that phase transformations can occur by the motion of transformation disconnections, of growth ledges, or by a combination of the two. Predictions of models for such transformations are shown to be consistent with a body of experimental evidence.]]>

DOI URL PMID [Cited within: 1]

WeChat

WeChat