1. Introduction

Magnesium is one of the lightest metals with abundant content on the earth, and has broad application prospects in the fields of transportation vehicles, electronic communications, and aerospace [[1], [2], [3]]. However, pure magnesium has poor mechanical properties, casting properties and corrosion resistance. Additional alloying elements are therefore introduced to improve properties and mitigate the shortcomings. The addition of alloying elements results in formation of intermetallic compounds (IMC) that affect the properties of the alloy and in-service performance of fabricated parts. For example, the AZ series is one of the most important commercialized magnesium alloy, where aluminum and zinc are common alloying elements [[4], [5], [6], [7], [8], [9], [10], [11], [12], [13]]. There are typically two ternary IMC can appear in the Mg-Al-Zn alloy system, i.e. the τ phase and ϕ phase [5,[14], [15], [16], [17], [18], [19], [20], [21]]. During the casting process, the two IMC segregate within the interdendritic regions and grain boundaries as second phases [9,11], and their high thermal stabilities effectively inhibit dislocation movement and grain boundary sliding at high temperatures [21]. Besides, the electrochemical efficiency of magnesium alloy containing τ and ϕ phase can be modified to meet the requirements for potential applications such as sacrificial anodes [7,10]. As important microstructural constituents, the size, shape and distribution of τ and ϕ phases in the AZ series magnesium alloys are key microstructural factors that control mechanical properties of the alloys. The morphological and size of the IMCs are controlled by the diffusion dynamics during solidification and post-solidification treatments. Therefore, it is of great necessity to investigate the formation and diffusion growth of the ternary τ and ϕ intermetallic compounds.

However, the elemental diffusion behavior in the ternary Mg-Al-Zn system were rarely studied, especially on ϕ and τ phase. Kammerer et al. [22] measured the ternary interdiffusion coefficients in Mg-Al-Zn solid solutions at 400 °C and 450 °C by the diffusion couple method. Cӗrmák and Stloukal [23] determined the diffusion coefficients of 65Zn in Mg17Al12 intermetallic and Mg-Al solution by continuous sectioning method and residual activity method. Wang et al. [24] evaluated the effect of Zn-rich coatings on the formation of IMC in Al-Mg dissimilar welds, and found that τ phase grew faster than the others. To the best of our knowledge, there is currently no experimental data on the diffusion growth of either ϕ or τ ternary phase in Mg-Al-Zn system in open literature. The lack of research data may be attributed to several reasons. In the experimental aspect, it is difficult to accurately control the composition of alloy samples to be within the τ phase region since Mg and Zn are very reactive. On the other hand, the annealed IMC phases are very brittle, making it difficult to prepare diffusion couple. The fabrication of ϕ phase may encounter with the same problem, and more importantly, the homogeneity range of ϕ phase is very narrow [5,16]. Besides, the moving interface problem generated during the diffusion growth of IMC layer cannot be easily considered in the estimation of interdiffusivity. In such case, the classical intersection method [25,26] for the determination of ternary interdiffusion coefficients with two diffusion channels loses its effectiveness.

The current work is devoted to studying the diffusion growth behavior of ϕ phase at 360 °C, while the works on the τ phase will be presented in our future work. Diffusion couples were fabricated at 360 °C and annealed for different times to detect the growth behavior of ϕ phase between pure Mg and τ phase. An in-situ observation technique was applied to further verify the accuracy of the detected growth constant. The elemental distribution in each diffusion bilayer was then measured to calculate the interdiffusion coefficients by numerical inverse method [[27], [28], [29]] within the determined homogeneity range of ϕ phase. A 3-D plot of composition-dependent interdiffusion coefficients of ϕ phase were finally obtained, which is applied to reproduce the experimentally observed composition profiles for future applications.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Sample preparation

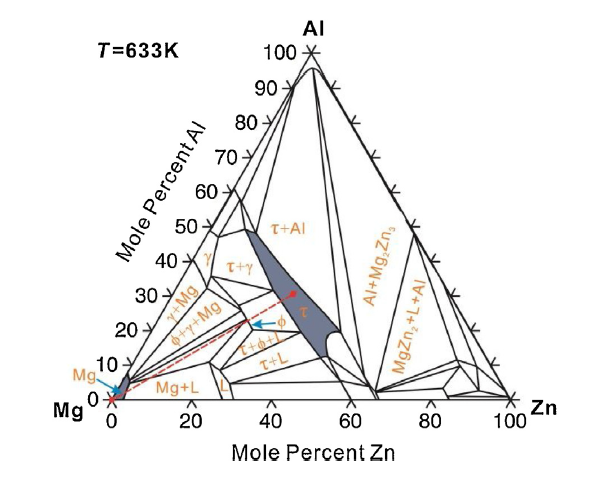

In order to study the diffusion growth behavior of ternary ϕ phase, a diffusion bilayer with Mg and τ phase as two end-members was designed. Fig. 1 gives the computed isothermal section of Mg-Al-Zn at 633 K (360 °C) according to the previous thermodynamic description of Mg-Al-Zn system using Thermo-Calc software [14,30]. The composition of two end-members of the diffusion couples are denoted as red dots, i.e. Mg and τ phase, while the red dashed line is the hypothetical diffusion path that goes across ϕ phase.

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

The computed isothermal section of Mg-Al-Zn at 633 K according to the previous thermodynamic description of Mg-Al-Zn system using Thermo-Calc software [14,30]. The composition of two end-members, i.e. Mg and τ phase, of the diffusion couples are shown as red dots. The red dashed line is the hypothetical diffusion path that goes across ϕ phase.

The blocks of 99.9 wt% high-purity Mg, 99.99 wt% high-purity Zn and 99.99 wt% high-purity Al were used as the raw materials for the preparation of τ phase alloys. During alloying, the resistance furnace was firstly heated up to 710 °C, and the Al blocks were placed in a stainless-steel crucible in the controlled atmosphere furnace. Mg and Zn were added in Al melts. Due to the high volatility of Mg and Zn, the additional 3.7 at.% Mg and 3.2 at.% Zn were put in the alloy to form τ phase after several attempts following the current process route. Mixed gas of SF6 and CO2 was introduced for protection since Mg is relatively flammable. After slag scraping and stirring, the sample was held at 720 °C for 25 min and then cooled down to 690 °C for casting. Graphite crucible with an outer diameter of 50 mm × 150 mm and wall thickness of 7 mm was used as the mold. The solidified alloy was annealed at 450 °C for 12 h in a resistance heating furnace back filled with Ar as the protective gas to improve the as-cast alloy homogeneity. The τ phase alloy ingot was then subject to wire-cutting into the blocks of 8 mm × 5 mm × 3 mm and annealing at 360 °C for 96 h. Both the X-ray Diffraction (XRD, Rigaku D-Max/2550VB+) powder analysis and the electron probe micro-analysis (EPMA, JXA-8230, JEOL, Japan) were performed to confirm that the prepared alloy is within the homogeneity region of τ phase as shown in Fig. 1.

Before clamping together the τ and Mg (8 mm × 5 mm × 3 mm, annealed at 360 °C) blocks in tantalum jig to form the diffusion couples, two surfaces in contact were metallographically polished to 0.05 μm alumina finish. The clamped assembly was then sealed in an evacuated quartz tube to avoid exposure to oxygen during the diffusion annealing. The quartz tube was evacuated and purged with Ar by three times before finally sealed with the inside pressure of about 10-3 torr. The diffusion couples were annealed at 360 °C in a tube furnace for 4, 16, 49 and 100 h with the temperature control of ±1 °C to generate IMC layers.

2.2. Sample analysis

The annealed diffusion couples were then unclamped from the Ta jigs and subjected to wire-cutting parallel to the diffusion direction. The cutting surface were metallographically prepared for analysis in a scanning electron microscope equipped with energy dispersive spectrometer (SEM-EDS, Zeiss EVO M10 and Oxford INCA X-Max50) to determine the growth of IMC layer after different annealing time. The composition of the newly formed IMC as well as the composition profile in each diffusion couple were also measured using EPMA. The in-situ observation of IMC growth was then performed to get accurate growth constant of the intermetallic layer using the High-temperature laser-scanning confocal microscopy (HTLSCM, VL2000DX-SVF17SP). The method had been successfully applied to the detection of IMC growth in the Al-Mg binary system [29]. During the current in-situ observation, the Mg-τ diffusion couples were placed in the heating container equipped for HTLSCM, which was back filled with Ar gas to prevent the samples from oxidation. The observation started with a heating process of 20 °C/min by the infrared radiation implemented in the heating container, and then held for 24 h at 360 °C before cooling to room temperature. The soaking temperature was within ±1 K thanks to the accurate temperature controlling system. Images of the growing intermetallic layer were saved every 0.5 s and merged into a video by the end of observation. When the heating stopped, the sample was cooled down to around 60 °C within 30 s. The time-dependent layer thicknesses of IMC phase developed in diffusion couples was detected directly.

2.3. Determination of interdiffusivity

Numerical inverse method was proved to be efficient in estimating the interdiffusion coefficients of IMC in the Al-Mg binary system [28,29], and is followed in the current work. This method requires the measured component profiles and parabolic growth constant (PGC) as the input. The interdiffusion coefficients and the properties of experimental measurement can then be related by the integral formula of Fick's law:

where x is the distance along the diffusion direction, $C_i^{ - \infty }$ and $C_i^{ + \infty }$ are the initial terminal compositions, and x0 is the location of Matano interface (plane). The left side of Eq. (1) is the definition formula of interdiffusion flux, i.e.:

The right side of Eq. (1) is the linear multiplication of diffusion coefficient $\tilde D_{ij}^n$ and composition gradient $\nabla {C_j}$, which can be expressed as ${J_{\text{i}}}.$.

The continuous function of interdiffusivity can be defined in the form of polynomial:

where pij are the parameters to determine during numerical inverse process. In the case of two interfaces formed when β phase is sandwiched by α and γ phases, the PGC of β phase can be expressed according to the mass balance [31],

where ${(DK)_{{\text{\alpha \beta }}}}$ term is the multiplication of ${D_{{\text{\alpha \beta }}}}$ and ${K_{{\text{\alpha \beta }}}}$ from $\alpha$ phase at $\alpha - \beta$ interface, ${D_{{\text{\alpha \beta }}}}$ is interdiffusivities matrix, and ${K_{{\text{\alpha \beta }}}}$ can be expressed as $\sqrt t {(\frac{{\partial C}}{{\partial x}})_{{\text{\alpha \beta }}}}$. The PGC can be accounted in the numerical inverse method as mathematical constrain when the accurate ${\tilde k_{\text{p}}}$ is experimentally determined. In the regression process, the deviation between ${\tilde J_i}$ and Ji as well as ${\tilde k_{\text{p}}}$ and kp is minimized to reach the optimum results. The method can deal with several diffusion couples fabricated under different conditions simultaneously. In the case of m diffusion couples, the loss function can be constructed as,

The regression process stops when the accuracy criterion of $\varepsilon \leqslant {10^{ - 22}}$ is reached [28], and the composition- and temperature-dependent interdiffusion coefficients are obtained.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Alloy of τ ternary phase

In order to confirm that the alloy blocks used in diffusion couples are single τ-phase alloys, the XRD powder analysis and the EPMA were performed. Table 1 gives the nominal and actual composition of the samples detected by EMPA. The differences between the nominal and actual Mg content is within 0.9 at.%, while the actual Zn and Al content show around 3 at.% deviation from their nominal values. This is mainly caused by the additional 3.7 at.% Mg and 3.2 at.% Zn to compensate the element volatilization during alloy preparation. Considering the large phase-field concentration of τ phase at 360 °C shown in Fig. 1, the current alloy compositions locate within the single-phase region of τ. Further verification can be seen from the resulting XRD diffraction patterns of the τ phase alloy annealed at 450 °C for 12 h as shown in Fig. 2, where each peak basically matches with its standard card. Based on these results, the blocks of τ single phase alloy can be confirmed and used for fabrication of the Mg-τ ternary diffusion couples.

Table 1 The nominal and actual compositions of the τ phase Alloys (at.%).

| No. | Nominal composition | Actual composition | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mg | Al | Zn | Mg | Al | Zn | |

| 1 | 39 | 30 | 31 | 39.42 | 27.45 | 33.13 |

| 2 | 39 | 30 | 31 | 39.55 | 26.97 | 33.47 |

| 3 | 39 | 30 | 31 | 39.88 | 26.14 | 33.98 |

| 4 | 39 | 30 | 31 | 39.69 | 26.15 | 34.16 |

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

XRD pattern of currently prepared ternary τ phase alloy annealed at 450 °C for 12 h.

3.2. Element distribution in diffusion couples after annealing

Fig. 3 gives the SEM images at the Mg-τ interface after different annealing time from 4 to 100 h at 360 °C. As expected, the formation and growth of ϕ ternary phase can be detected between the two end members of Mg and τ, and the increment of layer width can be seen as the annealing time increases. In order to measure the elements distribution in each phase region, Fig. 4 presents the EMPA results of a series of points selected on a line perpendicular to the phase interface along the diffusion direction. It can be seen that there is a compositional gradient formed within the pure Mg block, as a result of the diffusion of Zn and Al. The diffusion distance of Zn in Mg is longer than Al, implying faster diffusion of Zn than Al. This could be attributed to atomic size of Zn atom (0.138 nm) which is slightly less than the atomic size of Al atoms (0.143 nm) and the melting point of Zn (419 °C) being lower than Al (660 °C) [32,33]. The composition of the newly formed ϕ ternary phase layer is not constant across its thickness, indicating the dynamic nature of diffusion couple and instantaneous changes of compositional gradient across the interface with time. Concentration gradient can also be detected in the τ phase region, which is consistent with its large phase-field concentration [14]. Based on these experimental results, quantitative analysis may be performed on the diffusion growth behavior of ϕ phase at 360 °C to highlight the diffusion path and calculate the growth constant and interdiffusion coefficients.

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

SEM images of ϕ ternary phase at the Mg-τ interface after annealing at 360 °C for (a) 4 h, (b) 16 h, (c) 49 h and (d) 100 h.

Fig. 4.

Fig. 4.

EMPA result of element distribution in each phase region along diffusion direction after annealing at 360 °C for (a) 4 h, (b) 16 h, (c) 49 h and (d) 100 h. The open symbols are experimental data, while the solid lines are simulation results using the composition-dependent interdiffusion coefficients estimated in this work.

3.3. Diffusion path, growth constant and interdiffusion coefficients

3.3.1. Diffusion path

Fig. 5 shows the diffusion path of Mg-τ diffusion couple by plotting the composition profile on the isothermal section of Mg-Al-Zn system at 360 °C. Since the diffusion path of different annealing time shows very slight deviation from each other, only the experimental data of 100 h is shown representatively. Fig. 5(a) gives the complete diffusion path between the two end members. It can be seen in the Gibbs triangle that the diffusion route follows certain curve in each single-phase region. In Fig. 5(b), we can detect that the diffusion path in Mg-rich corner shows a raising trend towards the axis of Mg-Zn, meaning that the ratio of Zn and Al keeps changing within the whole diffusion path. The current experiment gives a maximum solid solubility of 2.73 at.% Zn and 3.78 at.% Al in pure Mg on the diffusion route. Fig. 5(c) and (d) is the enlarged region of ϕ and τ phase, where the composition also changes nonlinearly along the diffusion path. It should be noticed that there is a very narrow homogeneity range of ϕ phase form 22.87 at.% Zn and 20.95 at.% Al to 23.34 at.% Zn and 21.55 at.% Al on the diffusion route. As for the τ phase region, the two terminal compositions on the current diffusion path are 31.44 at.% Zn and 24.13 at.% Al, 34.16 at.% Zn and 26.15 at.% Al, respectively.

Fig. 5.

Fig. 5.

Diffusion path of 100 h heated Mg-τ diffusion couple along with the isothermal section of Mg-Al-Zn system at 360 °C: (a) whole composition range, (b) enlargement of the Mg-rich corner, (c) enlargement of the ϕ phase region and (d) enlargement of the τ phase region.

3.3.2. In-situ observation of parabolic growth of ϕ ternary phase

The accurate experimental value of PGC is important when applied to numerical inverse method to compute the composition-dependent interdiffusion coefficients of ϕ phase. In addition to the time-dependent layer thickness obtained from the SEM images, we performed in-situ hot stage microscopy observation of the diffusion couples annealed at 360 °C for 49 h. Following identical procedure presented in previous work of detecting intermetallic compounds growth for the Al-Mg diffusion couple [29], the diffusion growth of ϕ phase was examined by using HTLSCM. Fig. 6 gives a series of in-situ images of the IMC growth in the Mg-τ diffusion couple which was annealed at 360 °C for 49 h before being held 24 h at 360 °C in the hot stage microscope. The newly formed intermetallic layers grow continuously on both side of the original ϕ phase. The migration of both the Mg/ϕ and ϕ/τ interfaces indicates that the ϕ phase expands by consuming Mg as well as τ phase region. The increment of $\Delta W_{\text{l}}^\phi$ is slightly smaller than $\Delta W_{\text{r}}^\phi$, suggesting faster diffuison growth of ϕ phase into τ phase region than in Mg solid solution. The whole layer thickness increases from $W_0^\phi$=41.7 μm to ${W^\phi }$=50.3 μm within the observation period of 24 h at 360 °C in the hot stage microscope.

Fig. 6.

Fig. 6.

In-situ observation of the diffusion growth of ϕ phase at 360 °C using HTLSCM. $W_0^\phi$ is the initial layer width of ϕ phase at the starting point of observation, i.e. t0 = 3089 s. $\Delta W_{\text{r}}^\phi$ and $\Delta W_{\text{l}}^\phi$ are the increment of IMC layer thickness at the Mg/ϕ and ϕ/τ interfaces, respectively.

Fig. 7 gives the in-situ observation data of the layer thickness depending on the square root of annealing time together with the SEM data. Both two sets of data show a linear relationship, suggesting a diffusion-controlled growth of ϕ phase. Then PGC can be estimated as 8.587×10-15 m2/s by using the following formula [34],

Fig. 7.

Fig. 7.

In-situ observation data (open circle) of the layer thickness depending on the square root of annealing time together with the SEM data (open square). The dashed line is fitting result to the SEM data, while the solid line is the simulation result using current interdiffusion coefficients.

3.3.3. Calculation of interdiffusion coefficients

With the present experimental results of composition profiles and the PGC data, we can calculate the composition-dependent interdiffusion coefficients of ϕ phase at 360 °C by using the numerical inverse method [28,29]. In Fig. 8(a-d), the interdiffusion flux of Mg-τ diffusion couple annealed at 360 °C for 4 h, 16 h, 49 h and 100 h are simultaneously reproduced in each phase region along the diffusion path. The good agreement between current experimental data (square points) and the calculated interdiffusion flux (solid lines) indicates a reasonable composition-dependence of the interdiffuion coefficents. Fig. 9(a) gives the 3-D plots of composition-dependent interdiffusion coefficients of IMC and single phase regions along the Mg-τ diffusion path at 360 °C. The projection of interdiffusion coefficients on the concentration plane lies in the single phase region on the diffusion path. The magnitude of main interdiffusion coeffcients (${\tilde D_{{\text{MgMg}}}}$) in ϕ phase region is greater than that of τ phase, followed by that in the ternary solid-solution phase. The main interdiffusion coefficients ${\tilde D_{{\text{ZnZn}}}}$ in ϕ and τ phase are of close order of magnitude (10-14 m2/s), while that of ternary solid-solution phase is one order of magnitude (10 times) smaller. Fig. 9(b-d) presents closer observations of interdiffusivity in the Mg solid-solution, ϕ and τ phase region. In Fig. 9(b), the magnitude of ${\tilde D_{{\text{ZnZn}}}}$ is greater than ${\tilde D_{{\text{MgMg}}}}$ in the Mg single phase region, indicating that Zn diffuses faster than Mg at 360 °C. This is consistent with the previous experimental investigation of interdiffusion in ternary magnesium solid solutions of aluminum and zinc at 400 and 450 °C [22]. However, as shown in Fig. 9(c) and (d), ${\tilde D_{{\text{ZnZn}}}}$ is smaller than ${\tilde D_{{\text{MgMg}}}}$ in both of ϕ phase and τ phase. This is in contrary to the Mg solid solution phase, and suggesting a faster diffusion of Mg instead of Zn in the IMC. Such conclusion may be arrived at if the literature is consulted. However, such information is not available for ternary intermetallics, but there are reports for binary intermetallics where Mg diffusion in Mg17Al12 is greater than Zn diffusion in the same binary intermetallic, i.e. lower activation energy for Mg diffusion (147 kJ/mol, Mg vs. 154.3 kJ/mol, Zn) and greater interdiffusivity for Mg at 360 °C (3.45 × 10-15 m2/s, Mg vs. 2.81 × 10-15 m2/s, Zn) [23,35].

Fig. 8.

Fig. 8.

Interdiffusion flux of Mg-τ diffusion couples annealed at 360 °C for 4 h, 16 h, 49 h and 100 h in each phase region computed by numerical inverse methods (solid lines) along with the current experimental data (open symbols).

Fig. 9.

Fig. 9.

3-D plot of composition-dependent interdiffusion coefficients: (a) along the Mg-τ diffusion path; (b) in Mg solid-solution phase; (c) in ϕ phase; (d) in τ phase.

This may suggest that the diffusion of Zn could be the rate controlling parameter for the growth of φ-phase. However, such conclusion may be further elaborated if the interaction of Mg-Al-Zn is understood, i.e. the nature of interaction and possible exothermic reaction. This may justify as why Zn diffuses slower than Mg despite its smaller atomic size (0.159 nm, Mg vs. 0.138 nm, Zn) and the melting point of Zn (419 °C) being lower than Mg (650 °C). The other hypothesis may be the crystal lattice of the intermetallic and the fact that each element has a specific location within the crystal structure. This may affect the diffusion path and therefore the rate of growth of the intermetallic phase. However, the both hypotheses mentioned above require further study.

In order to verify the calculated interdiffusivities, simulation on both of the diffusional composition profiles and the PGC of IMC layer in Mg-τ diffusion couples should be performed to compare with experimental data. With the currently determined interdiffusivities, the composition profiles of Mg-τ diffusion couples annealed at 360 °C for different times are successfully reproduced, and is shown along with the measured data in Fig. 4(a-d). In Fig. 7, the currently simulated layer thickness of ϕ phase depending on the diffusion time is shown as a solid line, which exhibits a PGC (8.281×10-15 m2/s) close to the measured data. The presented agreement confirms the currently estimated interdiffusivities are reasonable.

4. Summary

In this work, we present a study on the diffusion growth behavior of ϕ phase at 360 °C. Four Mg-τ ternary diffusion couples were fabricated using the τ ternary phase alloy verified by XRD and EPMA, and were annealed at 360 °C for 4, 16, 49 and 100 h, respectively. The diffusion controlled parabolic growth of ϕ phase was successfully observed by using SEM and the in-situ observation technique of HTLSCM. The PGC of ϕ phase is determined to be 8.587×10-15 m2/s in the Mg-τ diffusion couple at 360 °C. The currently obtained diffusion path provides necessary information for determining the phase boundary in the Mg-Al-Zn isothermal section at 360 °C. Based on the obtained composition profiles and PGC data, the composition-dependent interdiffusivities were computed by the numerical inverse method using the present experimental data.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported financially by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (No. 2016YFB0701202), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 51801116 and 51901117), the Natural Science Foundation of Shandong Province (No. ZR2017BEM022) and the Youth Fund of Shandong Academy of Sciences (Nos. 2018QN0032 and 2019QN0023).

Reference

We report on the phase equilibria, the homogeneity range, the crystal and electronic structure of the Phi phase in the Al-Mg-Zn system. The homogeneity range is similar at 360 degrees C and 330 degrees C and has a wedgelike shape. Al and Zn vary about 13 at.% and Mg maximal 2.5 at.%. The crystal structure has been characterized by X-ray single crystal structure refinement at two compositions Al23.2Mg54.6Zn22.2 ((Al1.856Mg0.368Zn1.776)Mg-4, Z = 19, oP152, Pbcm, a = 8.9374(7) angstrom, b = 16.812(2) angstrom, c = 19.586(4) angstrom) and Al17.1Mg53.4Zn29.5 (Al1.368Mg0.272Zn2.360)Mg-4, a = 8.8822(3) angstrom, b = 16.7741(7) angstrom, c = 19.4789(8) angstrom). The structure contains four different types of layers stacked along the c axis which can be classified as pentagon-boat, boat, pentagon-triangle and square-triangle tilings. These tilings are decorated by Al and Zn centred icosahedra. The valence band structure can be described by a nearly free electron model except the 3d Zn contributions at lower energy. The large solubility for Al and Zn is caused by substitutional disorder at the icosahedral sites. Total energy calculations indicate, that the homogeneity range at higher temperatures splits up at 0 K into two ordered structures with compositions Al16Mg50Zn34 and Al10Mg50Zn40. (C) 2012 Elsevier Ltd.

WeChat

WeChat