In this work, three widely used commercial Zn alloys (ZA4-1, ZA4-3, ZA6-1) were purchased and prepared by hot extrusion at 200 °C. The microstructure, mechanical properties, corrosion behaviors, biocompatibility and hemocompatibility of Zn alloys were studied with pure Zn as control. Commercial Zn alloys demonstrated increased strength and superb elongation compared with pure Zn. Accelerated corrosion rates and uniform corrosion morphologies were observed in terms of commercial Zn alloys due to galvanic effects between Zn matrix and α-Al phases. 100% extracts of ZA4-1 and ZA6-1 alloys showed mild cytotoxicity while 50% extracts of all samples displayed good biocompatibility. Retardant cell cycle and inhibited stress fibers expression were observed induced by high concentration of Zn2+ releasing during corrosion. The hemolysis ratios of Zn alloys were lower than 1% while the adhered platelets showed slightly activated morphologies. In general, commercial Zn alloys possess promising mechanical properties, appropriate corrosion rates, significantly improved biocompatibility and good hemocompatibility in comparison to pure Zn. It is feasible to develop biodegradable metals based on commercial Zn alloys.

Biodegradable metals are expected to degrade progressively after fulfilling the mission to support tissue healing. During this period, the released corrosion products should be biologically tolerable and can be metabolized by the human body. During the last decade, researches have focused on magnesium, iron[1], [2], [3], [4] and [5] and their alloys as biodegradable materials. Magnesium is an essential element of human body and plays an important role in biological functions of human body. However, rapid degradation and loss of mechanical properties of Mg and its alloys are critical issues during implantation. Moreover, gas bubbles, which formed due to fast hydrogen evolution during corrosion of magnesium-based implants under physiological conditions, could exert negative effects on healing processes[6]. In contrast, the excellent corrosion resistance of iron and its alloys gives rise to relatively slow corrosion rates in body fluids, and their corrosion products are stable in long-term implantation[7] and [8]. In addition, the corrosion products of iron induce a stenosis of lumen and compromise the integrity of arterial wall. Therefore, great efforts such as addition of noble metals[9] and material modification[10] have been exerted to accelerate the degradation rates of iron.

Recently, increasing works have focused on zinc as an alternative to magnesium and iron. Zinc is often used as an alloying element in magnesium alloys and it shows beneficial effects on corrosion resistance and strength of magnesium[11], [12] and [13]. Zinc has a standard potential between magnesium and iron and may perform more appropriate degradation rates close to clinical requirements than magnesium and iron. The mechanical performances of Zn alloys and Mg alloys are similar. Moreover, zinc is an essential element of human body. Pure zinc wires were implanted into the abdominal aorta of Sprague-Dawley rats, and the subjects exhibited a promising corrosion behavior in vivo after 6-months implantation[14]. Moreover, no signs of restenosis-inflammatory response, localized necrosis, and intimal hyperplasia were observed[15]. Zn-Mg binary alloys were developed and Zn-1Mg exhibited the optimal mechanical properties[16]. Besides, the 1-day extracts of Zn-Mg alloys were neither mutagenic nor genotoxic for U-2 OS and L929 cell lines[17]. The Zn-1

For applications as implants, toxicity of materials is a critical issue. Zinc is a nutritionally essential element in human body. 85% of the whole body zinc is found in muscle and bone. Zinc plays a crucial role in diverse biological functions from enzymatic catalysis to cellular neuronal systems. Zinc participates in the functions of plenty of metalloproteins including members of oxido-reductase, hydrolase ligase, and lyase family and cooperates with copper to activate superoxide and dismutase or phospholipase C[29]. The recommended dietary allowance (RDA) for zinc is 15 mg/day, and 40 mg/day is set as the upper limit[30]. Zinc deficiency may severely affect the homeostasis of a biological system. However, zinc is also a ubiquitous element in human body, and its excess can have severe negative impacts such as copper deficiency and impaired immune functions[31]. Copper is another essential element for humans. It is a component of numerous enzymes and affects a wide variety of metabolic processes[32]. Alterations in copper metabolism have potential connections to inflammation, immune system, cancer, atherosclerosis and anemia[33]. In contrast, excess copper can generate free radicals which induce lipid peroxidation and interfere with bone metabolism[31]. As for aluminum, its relationship with neuro-toxicity is still under debate[34] and [35].

In the present study, ZA4-1, ZA4-3 and ZA6-1 alloys were chosen as experimental materials due to their widespread applications and low contents of Al. Microstructure, mechanical performances, in vitro corrosion behaviors and biological characteristics of Zn alloys were carried out. Materials were hot extruded to achieve high mechanical performances and pure Zn was set as control. For in vitro cell tests, human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) were selected. The biocompatibility of commercial Zn alloys was evaluated by indirect assay, flow cytometry analysis and cell morphologies were taken by a fluorescent microscope. The objective of this study is to evaluate the feasibility of commercial Zn alloys as potential biodegradable metals.

The high-pure Zn (HP-Zn, 99.99%, Huludao Zinc Industry Co. China) and commercial Zn alloys (ZA4-1, ZA4-3, ZA6-1 alloys, Dongguan Xin Liang Metal Materials Co. China) were used as raw materials. The chemical compositions of studied materials are given in

X-ray diffractometer (XRD, Rigaku DMAX 2400, Japan) using Cu

The tensile and uniaxial compression testing samples were cut from the extruded cylinders according to ASTM standards. The tensile and uniaxial compression tests were carried out in a universal material test machine (Instron 5969, USA) at room temperature in accordance with ASTM-E8M-09 and ASTM E9-89a standards, respectively. Five duplicate specimens were taken for each group. The hardness of experimental samples was determined by a digital Vickers microhardness tester (HMV-2T, Shimadzu Corporation, Japan) with a 0.98 N load and 15 s dwell time.

The electrochemical tests were conducted with an electrochemical working station (Autolab, Metrohm, Switzerland) at room temperature in Hank's solution (NaCl 8.00 g L-1, KCl 0.40 g L-1, CaCl2 0.14 g L-1, NaHCO3 0.35 g L-1, glucose 1.00 g L-1, MgCl2⋅6H2O 0.10 g L-1, MgSO4⋅7H2O 0.06 g L-1, Na2HPO4⋅12H2O 0.06 g L-1 and KH2PO4 0.06 g L-1, pH 7.4). Before electrochemical tests, surfaces of samples were polished. A three-electrode cell with a platinum counter-electrode and a saturated calomel electrode (SCE) as the reference electrode was utilized for electrochemical tests. The open-circuit potential (OCP) of each sample was monitored for 5400 s. Afterwards, potentiodynamic polarization tests were carried out at a scanning rate of 1 mV/s. At least five measurements were taken for each sample group. Corrosion parameters including open-circuit potential (OCP), corrosion potential (

2.5.1. Cytotoxicity test

The cytotoxicity test was carried out according to ISO 10993-5:2009. Human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM), 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 100 U/mL penicillin and 100 µg/mL streptomycin at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2. The cytotoxicity test was evaluated using the 100% and 50% extracts of metal plates, prepared with a surface area to extraction medium ratio of 1.25 mL/cm2 in a humidified atmosphere, with 5% CO2 at 37 °C for 24 h. The supernatant fluid was withdrawn, centrifuged and kept at 4 °C prior to use. Cells were incubated in 96-well culture plates at a density of 3 × 104 cells/mL in each well and incubated for 24 h to allow attachment. The medium was then replaced with 100 µL extracts of pure Zn, ZA4-1, ZA4-3 and ZA6-1 groups. DMEM medium was used as control. After 1, 2 and 4 days of incubation, 10 µL Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8, Dojindo, Kumamoto, Japan) was added to each well and incubated for 1 h. The spectrophotometrical absorbance of samples was measured at 450 nm using a microplate reader (Bio-RAD680). Zn, Al, Cu, Mg ion concentrations in extracts were measured by ICP-OES and ICP-MS. The cells were obtained from ATCC and maintained in our lab.

2.5.2. Flow cytometry analysis of cell cycle

Human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM), 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 100 U/mL penicillin and 100 µg/mL streptomycin at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2. Flow cytometry analysis (FACSAria II, BD Bioscience, US) with 7-Amino-Actinomycin D (7-AAD, BD Pharmingen, US) staining was performed to evaluate the effect of alloy extracts on the cell cycle of HUVECs. Briefly, HUVECs were seeded into 6-well plates with 5 × 104 cells/well and cultured until confluence, and then the media was replaced with DMEM (without FBS). After serum starvation for 22 h, cells were treated with extracts for 24 h. After the cultivation period, cells were harvested, washed once with cold phosphate buffered saline (PBS), fixed in ice-cold 70% ethanol and stored at 4 °C. Prior to analysis, cells were treated with RNase A at 37 °C and stained with 10 µL 7-AAD in the dark. Next, flow cytometry was conducted, and using BD FACSDiva software v6.1.3 (BD Bioscience, USA) all data were acquired and analyzed. The ratios of cells in G0/G1, S and G2/M phases were calculated.

2.5.3. Confocal laser scanning microscopy

FITC Phalloidin (Yeasen, China) and Hoechst 33258 (Sigma, Germany) dyes were used to visualize actin microfilament and nuclei. Metal plates were placed flat in the bottom of 24-well plates, 5 × 104/well HUVECs were seeded on the surfaces of metal plates and incubated for 24 h at 37 °C with 5% CO2. Cells seeded in cover glass-bottom dishes (SPL, Korea) were used as control. HUVECs were fixed on metal plates using formaldehyde for 30 min at 25 °C and then washed thoroughly with PBS. After that, cells were permeabilized using PBS containing 0.1% Triton X-100 to allow the dyes to penetrate the nuclei. Then, 200 µL of FITC Phalloidin was added and incubated for 30 min, then washed with PBS twice. Subsequently, 200 µL Hoechst 33258 was added and incubated for 10 min. Finally, metal plates were inverted in cover glass-bottom dishes and viewed under an inverted confocal laser scanning microscope (CLSM, Leica TCS SP5, Germany).

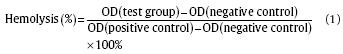

Healthy human blood from a volunteer was applied to conduct hemolysis and platelet adhesion tests. For hemolysis test, healthy human blood containing sodium citrate (3.8 wt%) in the ratio of 9:1 was taken and diluted with normal saline (4:5 ratio by volume). Specimens were dipped in centrifuge tubes containing 10 mL of normal saline that were previously incubated at 37 °C for 30 min. Then 0.2 mL of diluted blood was added to a centrifuge tube and then incubated for 60 min at 37 °C. Similarly, normal saline solution was set as a negative control and deionized water as a positive control. Afterwards, all tubes were centrifuged for 5 min at 3000 rpm, and the supernatant was carefully removed and transferred to 96-well cell culture plates for spectroscopic analysis at 545 nm using a microplate reader (Bio-RAD680). The hemolysis rates were calculated according to Eq. (1):

For platelet adhesion test, platelet-rich plasma (RPR) was prepared by centrifuging the whole blood for 10 min at a rate of 1000 rpm. The RPR was overlaid atop specimens and incubated at 37 °C for 1 h. Samples were rinsed with PBS to remove the nonadherent platelets. The adhered platelets were fixed in 2.5% glutaraldehyde solutions for 2 h at room temperature followed by dehydrated in a gradient ethanol/distilled water mixture (50%, 60%, 70%, 80%, 90%, 100%) for 10 min each and finally dried in air. The morphologies of adhered platelets were observed by SEM (S-4800, Hitachi, Japan).

Statistical analysis was performed with SPSS 18.0 for windows software (SPSS Inc. Chicago, USA). One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Turkey post hoc tests was used to statistically analysis the data. A p-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

The microstructure of pure Zn and Zn alloys observed by SEM are illustrated in

Fig. 2. SEM images of the microstructure of pure Zn and Zn alloys: (a) pure Zn, (b) ZA4-1 alloy, (c) ZA4-3 alloy, (d) ZA6-1 alloy. Matrix and second phases in images are indicated by *.

Chemical compositions of second phases and matrix indicated by * in

The mechanical properties of pure Zn and Zn alloys are displayed in

Fig. 3. Mechanical properties of pure Zn and Zn alloys: (a) yield strength, ultimate tensile strength and elongation, (b) compressive yield strength and ultimate compressive strength, (c) tensile stress-stain curves, (d) compressive stress-stain curves, *p < 0.5, compared with pure Zn.

With the addition of alloying elements Al, Cu and Mg, overall improvements in mechanical performances are seen in Zn alloys. The Al-rich phase (α-Al) is a hard and brittle intermetallic compound and the uniformly distributed α-Al results in a second phase strengthening effect. Moreover, the dissolution of Cu in Zn matrix creates a solid solution strengthening effect. As a result, the above-mentioned strengthening effects contribute to the increased strength and hardness of Zn alloys compared with pure Zn. As for the excellent plasticity, after alloying and hot extrusion, α-Al particles are mostly spherical in-shape and decompose mainly along the η-Zn boundaries. During tension, the grain boundary sliding, which is generally the predominant mode of deformation during plastic flow, can easily take place along inter-phase boundaries. Moreover, the α/η interface has weaker binding with original Zn crystal and grain boundary sliding can take place easily on these phase boundaries[38]. All these reasons lead to the superb plasticity of Zn alloys.

Potentiodynamic polarization curves of pure Zn and Zn alloys examined in Hank's solution are shown in

The corrosion parameters, including corrosion current density (

Note: numbers in the brackets represent the standard deviation.

Fig. 6. SEM images of pure Zn and Zn alloys after electrochemical tests: (a) pure Zn, (b) ZA4-1 alloy, (c) ZA4-3 alloy, (d) ZA6-1 alloy.

Chemical compositions of selected areas in

Fig. 8. Elemental (EDS) maps for typical corroded regions in pure Zn and Zn alloys: (a) pure Zn, (b) ZA4-1 alloy, (c) ZA4-3 alloy, (d) ZA6-1 alloy.

In the nearly neutral solution like Hank's solution, the anodic reaction of Zn is dissolution of the metal (Eq. (2)), and the cathodic reaction is based on the reduction of oxygen (Eq. (3)) which is different from the hydrogen evolution reaction that happens in the corrosion of Mg alloys[17]. Zinc ions react with hydroxyl ions, which gives rise to the formation of zinc hydroxide rust (Eq. (4))[39]:

Anodic reaction:

Zn→Zn2++2e.Zn→Zn2++2e.

Cathodic reaction:

2H2O+O2+4e→4OH-.

Formation of zinc hydroxide rust:

Zn2++2OH-→Zn(OH)2.

Corrosion products of pure Zn and Zn alloys after electrochemical tests are predominantly composed of Zn, Al or O and other elements such as C and P (

The viability of HUVECs cultured in extraction mediums of pure Zn and Zn alloys for 1, 2 and 4 days is shown in

Fig. 9. Cell viability after culturing in extraction mediums of pure Zn and Zn alloys for 1, 2 and 4 days: (a) 100% extracts, (b) 50% extracts, *p < 0.5, compared with pure Zn.

The ion concentrations of 100% extraction mediums are listed in

The influence of extracts of pure Zn and ZA4-1, ZA4-3, ZA6-1 alloys on cell cycle progression is studied using a flow cytometer to analyze cell percentages in each cycle phase: G1/G0, S and G2/M and results are shown in

Fig. 10. Cell cycle analysis of HUVECs cultured in extraction mediums of pure Zn and Zn alloys for 24 h: (a) control group, (b) pure Zn, (c) ZA4-1 alloy, (d) ZA4-3 alloy, (e) ZA6-1 alloy, (f) graphic representations of the cell cycle distributions of HUVECs.

The morphologies and cell cytoskeletal reorganizations of HUVECs seeded on the surfaces of samples are shown in

The hemolysis percentages of experimental samples are shown in

Commercial Zn alloys possess a promising combination of strength and plasticity. The elongation of Zn alloys reported in this study (111%-169%) indicates superplasticity at room temperature. This property endows commercial Zn alloys a great advantage in fabricating implants with complex shapes. Biocompatibility is a critical issue for biodegradable metals. The cytotoxicity of pure Zn and Zn alloys have been examined through both direct and indirect tests. A cytotoxic effect is observed in 100% extracts of both pure Zn and Zn alloy groups, this effect could be induced by the released ions from chemical reactions during corrosion. In the cytotoxicity test, the cell viability after 1 d of intervention was in the following order, ZA6-1 > ZA4-1 > ZA4-3 > pure Zn, and the corresponding concentrations of Zn2+ in these extracts were 146.3, 146.5, 165.8 and 188.3 µM/L, respectively. Since significant lower concentrations of the alloy ions (Cu2+, Al3+, Mg2+) were in the extracts and there was no significant difference among these groups, Zn2+ should be responsible for the various toxicities of the Zn-based materials. An increasing cytotoxic effect with increased Zn2+ concentrations, which is generally consistent with several studies, can be seen[48] and [49]. However, the 50% extracts of materials all showed great cell viabilities, which indicated no cytotoxicity of extracts after dilution. It has been reported that Zn2+ exhibits a biphasic effect at different ion concentrations[50]. Zn2+ concentrations higher than 100 µM decreases the viability of HCECs significantly, while low concentrations (0—60 µM) of Zn2+ promotes viability, proliferation, adhesion and migration of cells. Furthermore, the maximum safe Zn2+ concentrations for the U-2 OS and L929 cell lines are 120 µM and 80 µM, respectively[17]. Moreover, excess Cu2+ and Al3+ might cause cytotoxicity as well. However, the ion concentrations of Cu2+ and Al3+ in extracts are negligible (

Cell cycle is a series of events during replication of eukaryotic cells, which is divided into three periods: interphase, the mitotic phase, and cytokinesis. There are three checkpoints to ensure the proper division of the cell: the G1 checkpoint, the G2/M checkpoint, and the metaphase checkpoint. Based on our data, more cells cultured in extracts of pure Zn and ZA4-3 alloy are arrested in G1 phase, and the percentages of S phase decrease with increasing Zn2+ concentrations. This finding suggests that high concentrations of Zn2+ are probably related to retardant of cell cycle. Zn2+ can efficiently affect cell cycle progression of MDAMB231 cells by inhibiting cells in G1 phase from moving to the subsequent S phase. Moreover, cell cycle is affected by Zn2+ in a dose-dependent manner. Cell population in S phase decreases dramatically when concentrations of Zn2+ reach 150 µM[59]. The mechanism of how Zn2+ influence cell cycle is complicated and could be simply explained by the influence of Zn2+ on cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 1 (p21). Excess Zn2+ can upregulate p21 protein and mRNA levels as well as p21 promoter activity[60]. Thus, over-expressed p21 causes the arrest of cell cycle in G1 and G2/M and leads to a profound inhibition of S-phase progression[61].

The cytoskeleton is an interconnected network of filamentous polymers and regulatory proteins. It is equipped to resist deformation, transport intracellular cargo and change shape during movement. There are three main types of cytoskeletal polymer: actin filaments, microtubules and intermediate filaments, they control the shapes and mechanics of cells together[62]. Various factors can influence local organization of filaments in the networks. The intensity of actin microfilaments, microtubules and cytoskeletal alterations in HUVECs after 24 h of incubation in different extracts are recorded. The expression of stress fibers is inhibited in all experimental groups, which indicates that high concentrations of Zn2+ might account for the suppressed expression of actin. This finding is in agreement with a previous report that Zn2+ inhibits the expression of stress fibers at high concentrations[50]. In addition, high concentrations of Zn2+ have been proved to disturb the dynamicity of cell structures and cause morphological changes[49]. The reasons mentioned above explain the different morphologies of HUVECs between control group and material groups. The molecular mechanism of how Zn2+ modulates actin networks in endothelial cells is still unclear, further investigation need to be carried out.

The findings in this study suggest that commercial Zn alloys with additions of Al, Cu and Mg display promising mechanical performances and good biocompatibility. The strength of commercial Zn alloys and novel biodegradable Zn alloys are comparable. As for the plasticity, commercial Zn alloys display superb elongations (111%-169%), while the elongations of novel biodegradable Zn alloys like Zn-Mg, Zn-Ca and Zn-Sr are below 20%[17] and [18]. This property is critical when fabricating implants that need severe deformation like cardiovascular stents or sutures. As for the biological properties, the 100% extracts of commercial Zn alloys exhibit cytotoxic effects on HUVECs while ZA4-1 and ZA4-3 alloys demonstrate a significantly improved biocompatibility compared with pure Zn. However, no cytotoxicity is observed after dilution of extracts. Moreover, 100% extracts of Zn-Mg alloy also exhibit cytotoxic effects on U-2 OS cells, L929 cells and NHOst cells[17] and [49]. In fact, for both commercial Zn alloys and novel biodegradable Zn alloys, the cytotoxic effect should not be a problem because the

The feasibility of commercial Zn alloys as biodegradable metals was evaluated in the present study. In the as-extruded state,

This work was supported by the National Basic Research Program of China (973 Program) (Grant Nos. 2012CB619102 and 012CB619100), National Science Fund for Distinguished Young Scholars (Grant No. 51225101), National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos. 51431002 and 31170909), the NSFC/RGC Joint Research Scheme (Grant No. 51361165101), State Key Laboratory for Mechanical Behavior of Materials (Grant No. 20141615), and Beijing Municipal Science and Technology Project (No. Z141100002814008).

The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

| [1] |

@article{4350019, author = {De Witte, Virginie and Govaerts, Willy and Kuznetsov, Yuri A and Meijer, Hil GE}, issn = {0167-2789}, journal = {PHYSICA D-NONLINEAR PHENOMENA}, keyword = {DYNAMICAL-SYSTEMS,Fold-Neimark-Sacker,FIXED-POINTS,ODES,EQUILIBRIA,ENRICHMENT,PARADOX,MATCONT,MAPS,PERIODIC NORMALIZATION,Flip-Neimark-Sacker,Double Neimark-Sacker,4-torus,3-torus,Normal form,CODIM 2 BIFURCATIONS}, language = {eng}, pages = {126--141}, title = {Analysis of bifurcations of limit cycles with Lyapunov exponents and numerical normal forms}, url = {http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.physd.2013.12.002}, volume = {269}, year = {2014}, }

|

| [2] |

Magnesium alloys attracted great attention as a new kind of degradable biomaterials. One research direction of biomedical magnesium alloys is based on the industrial magnesium alloys system, and another is the self-designed biomedical magnesium alloys from the viewpoint of biomaterials. The mechanical, biocorrosion properties and biocompatibilities of currently reported Mg alloys were summarized in the present paper, with the mechanical properties of bone tissue, the healing period postsurgery, the pathophysiology and toxicology of the alloying elements being discussed. The strategy in the future development of biomedical Mg alloys was proposed.

|

| [3] |

Biodegradable metals are breaking the current paradigm in biomaterial science to develop only corrosion resistant metals. In particular, metals which consist of trace elements existing in the human body are promising candidates for temporary implant materials. These implants would be temporarily needed to provide mechanical support during the healing process of the injured or pathological tissue. Magnesium and its alloys have been investigated recently by many authors as a suitable biodegradable biomaterial. In this investigative review we would like to summarize the latest achievements and comment on the selection and use, test methods and the approaches to develop and produce magnesium alloys that are intended to perform clinically with an appropriate host response.

|

| [4] |

<h2 class="secHeading" id="section_abstract">Abstract</h2><p id="">As a lightweight metal with mechanical properties similar to natural bone, a natural ionic presence with significant functional roles in biological systems, and in vivo degradation <em>via</em> corrosion in the electrolytic environment of the body, magnesium-based implants have the potential to serve as biocompatible, osteoconductive, degradable implants for load-bearing applications. This review explores the properties, biological performance, challenges and future directions of magnesium-based biomaterials.</p>

|

| [5] |

<h2 class="secHeading" id="section_abstract">Abstract</h2><p id="">As bioabsorbable materials, magnesium alloys are expected to be totally degraded in the body and their biocorrosion products not deleterious to the surrounding tissues. It's critical that the alloying elements are carefully selected in consideration of their cytotoxicity and hemocompatibility. In the present study, nine alloying elements Al, Ag, In, Mn, Si, Sn, Y, Zn and Zr were added into magnesium individually to fabricate binary Mg–1X (wt.%) alloys. Pure magnesium was used as control. Their mechanical properties, corrosion properties and in vitro biocompatibilities (cytotoxicity and hemocompatibility) were evaluated by SEM, XRD, tensile test, immersion test, electrochemical corrosion test, cell culture and platelet adhesion test. The results showed that the addition of alloying elements could influence the strength and corrosion resistance of Mg. The cytotoxicity tests indicated that Mg–1Al, Mg–1Sn and Mg–1Zn alloy extracts showed no significant reduced cell viability to fibroblasts (L-929 and NIH3T3) and osteoblasts (MC3T3-E1); Mg–1Al and Mg–1Zn alloy extracts indicated no negative effect on viabilities of blood vessel related cells, ECV304 and VSMC. It was found that hemolysis and the amount of adhered platelets decreased after alloying for all Mg–1X alloys as compared to the pure magnesium control. The relationship between the corrosion products and the in vitro biocompatibility had been discussed and the suitable alloying elements for the biomedical applications associated with bone and blood vessel had been proposed.</p>

|

| [6] |

This study investigates the bone and tissue response to degrading magnesium pin implants in the growing rat skeleton by continuous in vivo microfocus computed tomography (mu CT) monitoring over the entire pin degradation period, with special focus on bone remodeling after implant dissolution. The influence of gas release on tissue performance upon degradation of the magnesium implant is also addressed. Two different magnesium alloys - one fast degrading (ZX50) and one slowly degrading (WZ21) - were used for evaluating the bone response in 32 male Sprague-Dawley rats. After femoral pin implantation mu CTs were performed every 4 weeks over the 24 weeks of the study period. ZX50 pins exhibited early degradation and released large hydrogen gas volumes. While considerable callus formation occurred, the bone function was not permanently harmed and the bone recovered unexpectedly quickly after complete pin degradation. WZ21 pins kept their integrity for more than 4 weeks and showed good osteoconductive properties by enhancing bone accumulation at the pin surface. Despite excessive gas formation, the magnesium pins did not harm bone regeneration. At smaller degradation rates, gas evolution remained unproblematic and the magnesium implants showed good biocompatibility. Online mu CT monitoring is shown to be suitable for evaluating materials degradation and bone response in vivo, providing continuous information on the implant and tissue performance in the same living animal. (C) 2011 Acta Materialia Inc. Published by Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

|

| [7] |

ABSTRACT A series of unconventional approaches has been developed at Michigan Technological University, which is able to screen candidate materials for use in bioabsorbable (or bioresorbable) stents by reducing the scale of necessary animal studies and the complexity of biocorrosion analyses. Using a novel in vivo approach, materials formed into a simplified wire geometry were implanted into the wall of the abdominal aorta of rodents for several weeks or months to measure the extent of in vivo degradation, quantify mechanical strength over time, characterize the resulting products, and assess biocompatibility. An in vitro method was developed to identify bioabsorbable candidate materials, reproduce the corrosion products formed in vivo, and predict the degradation rate of stent materials. To accomplish this goal, wires were encapsulated in an extracellular matrix and corroded in cell culture media in vitro. Encapsulation of the wires in vitro was necessary in order to mimic in vivo stent encapsulation within a neo-intima. Alternatively, accelerated in vitro corrosion for materials with very low corrosion rates was accomplished by exposing fibrin-coated wires to a steady flow of cell culture media. After in vivo and in vitro tests, wires were subjected to tensile testing to quantify the rate of material degradation and loss of mechanical strength.

|

| [8] |

<h2 class="secHeading" id="section_abstract">Abstract</h2><p id="">Biodegradable stents have shown their potential to be a valid alternative for the treatment of coronary artery occlusion. This new class of stents requires materials having excellent mechanical properties and controllable degradation behaviour without inducing toxicological problems. The properties of the currently considered gold standard material for stents, stainless steel 316L, were approached by new Fe–Mn alloys. The degradation characteristics of these Fe–Mn alloys were investigated including in vitro cell viability. A specific test bench was used to investigate the degradation in flow conditions simulating those of coronary artery. A water-soluble tetrazolium test method was used to study the effect of the alloy’s degradation product to the viability of fibroblast cells. These tests have revealed the corrosion mechanism of the alloys. The degradation products consist of metal hydroxides and calcium/phosphorus layers. The alloys have shown low inhibition to fibroblast cells’ metabolic activities. It is concluded that they demonstrate their potential to be developed as degradable metallic biomaterials.</p>

|

| [9] |

[Cited within:1]

|

| [10] |

[Cited within:1]

|

| [11] |

<h2 class="secHeading" id="section_abstract">Abstract</h2><p id="">In this study a binary Mg–Zn magnesium alloy was researched as a degradable biomedical material. An Mg–Zn alloy fabricated with high-purity raw materials and using a clean melting process had very low levels of impurities. After solid solution treatment and hot working the grain size of the Mg–Zn alloy was finer and a uniform single phase was gained. The mechanical properties of this Mg–Zn alloy were suitable for implant applications, i.e. the tensile strength and elongation achieved were ∼279.5 MPa and 18.8%, respectively.</p><p id="">The results of in vitro degradation experiments including electrochemical measurements and immersion tests revealed that the zinc could elevate the corrosion potential of Mg in simulated body fluid (SBF) and reduce the degradation rate. The corrosion products on the surface of Mg–Zn were hydroxyapatite (HA) and other Mg/Ca phosphates in SBF. In addition, the influence caused by in vitro degradation on mechanical properties was studied, and the results showed that the bending strength of Mg–Zn alloy dropped sharply in the earlier stage of degradation, while smoothly during the later period.</p><p id="">The in vitro cytotoxicity of Mg–Zn was examined. The result 0–1 grade revealed that the Mg–Zn alloy was harmless to L-929 cells. For in vivo experiments, Mg–Zn rods were implanted into the femoral shaft of rabbits. The radiographs illustrated that the magnesium alloy could be gradually absorbed in vivo at about 2.32 mm/yr degradation rate obtained by weight loss method. Hematoxylin and eosin (HE) stained section around Mg–Zn rods suggested that there were newly formed bone surrounding the implant.</p><p id="">HE stained tissue (containing heart, liver, kidney and spleen tissues) and the biochemical measurements, including serum magnesium, serum creatinine (CREA), blood urea nitrogen (BUN), glutamic-pyruvic transaminase (GPT) and creatine kinase (CK) proved that the in vivo degradation of Mg–Zn did not harm the important organs. Moreover, no adverse effects of hydrogen generated by degradation had been observed and also no negative effects caused by the release of zinc were detected. These results suggested that the novel Mg–Zn binary alloy had good biocompatibility in vivo.</p>

Magsci

[Cited within:1]

|

| [12] |

<h2 class="secHeading" id="section_abstract">Abstract</h2><p id="">Binary Mg–Ca alloys with various Ca contents were fabricated under different working conditions. X-ray diffraction (XRD) analysis and optical microscopy observations showed that Mg–<em>x</em>Ca (<em>x</em> = 1–3 wt%) alloys were composed of two phases, α(Mg) and Mg<sub>2</sub>Ca. The results of tensile tests and <em>in vitro</em> corrosion tests indicated that the mechanical properties could be adjusted by controlling the Ca content and processing treatment. The yield strength (YS), ultimate tensile strength (UTS) and elongation decreased with increasing Ca content. The UTS and elongation of as-cast Mg–1Ca alloy (71.38 ± 3.01 MPa and 1.87 ± 0.14%) were largely improved after hot rolling (166.7 ± 3.01 MPa and 3 ± 0.78%) and hot extrusion (239.63 ± 7.21 MPa and 10.63 ± 0.64%). The <em>in vitro</em> corrosion test in simulated body fluid (SBF) indicated that the microstructure and working history of Mg–<em>x</em>Ca alloys strongly affected their corrosion behaviors. An increasing content of Mg<sub>2</sub>Ca phase led to a higher corrosion rate whereas hot rolling and hot extrusion could reduce it. The cytotoxicity evaluation using L-929 cells revealed that Mg–1Ca alloy did not induce toxicity to cells, and the viability of cells for Mg–1Ca alloy extraction medium was better than that of control. Moreover, Mg–1Ca alloy pins, with commercial pure Ti pins as control, were implanted into the left and right rabbit femoral shafts, respectively, and observed for 1, 2 and 3 months. High activity of osteoblast and osteocytes were observed around the Mg–1Ca alloy pins as shown by hematoxylin and eosin stained tissue sections. Radiographic examination revealed that the Mg–1Ca alloy pins gradually degraded <em>in vivo</em> within 90 days and the newly formed bone was clearly seen at month 3. Both the <em>in vitro</em> and <em>in vivo</em> corrosion suggested that a mixture of Mg(OH)<sub>2</sub> and hydroxyapatite formed on the surface of Mg–1Ca alloy with the extension of immersion/implantation time. In addition, no significant difference (<em>p</em> > 0.05) of serum magnesium was detected at different degradation stages. All these results revealed that Mg–1Ca alloy had the acceptable biocompatibility as a new kind of biodegradable implant material. Based on the above results, a solid alloy/liquid solution interface model was also proposed to interpret the biocorrosion process and the associated hydroxyapatite mineralization.</p>

Magsci

[Cited within:1]

|

| [13] |

Nature Materials journal covers a range of topics within materials science, from materials engineering and structural materials (metals, alloys, ceramics, composites) to organic and soft materials (glasses, colloids, liquid crystals, polymers).

|

| [14] |

Zinc is proposed as an exciting new biomaterial for use in bioabsorbable cardiac stents. Not only is zinc a physiologically relevant metal with behavior that promotes healthy vessels, but it combines the best behaviors of both current bioabsorbable stent materials: iron and magnesium. Shown here is a composite image of zinc degradation in a murine (rat) artery.

|

| [15] |

[Cited within:2]

|

| [16] |

In the present work Zn-Mg alloys containing up to 3 wt.% Mg were studied as potential biodegradable materials for medical use. The structure, mechanical properties and corrosion behavior of these alloys were investigated and compared with those of pure Mg, AZ91HP and casting Zn-Al-Cu alloys. The structures were examined by light and scanning electron microscopy (SEM), and tensile and hardness testing were used to characterize the mechanical properties of the alloys. The corrosion behavior of the materials in simulated body fluid with pH values of 5, 7 and 10 was determined by immersion tests, potentiodynamic measurements and by monitoring the pH value evolution during corrosion. The surfaces of the corroded alloys were investigated by SEM, energy-dispersive spectrometry and X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy. It was found that a maximum strength and elongation of 150 MPa and 2%, respectively, were achieved at Mg contents of approximately 1 wt.%. These mechanical properties are discussed in relation to the structural features of the alloys. The corrosion rates of the Zn-Mg alloys were determined to be significantly lower than those of Mg and AZ91HP alloys. The former alloys corroded at rates of the order of tens of microns per year, whereas the corrosion rates of the latter were of the order of hundreds of microns per year. Possible zinc doses and toxicity were estimated from the corrosion behavior of the zinc alloys. It was found that these doses are negligible compared with the tolerable biological daily limit of zinc. (C) 2011 Acta Materialia Inc. Published by Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

|

| [17] |

Zn–(0–1.6)Mg (in wt.%) alloys were prepared by hot extrusion at 30002°C. The structure, mechanical properties and in vitro biocompatibility of the alloys were investigated. The hot-extruded magnesium-based WE43 alloy was used as a control. Mechanical properties were evaluated by hardness, compressive and tensile testing. The cytotoxicity, genotoxicity (comet assay) and mutagenicity (Ames test) of the alloy extracts and ZnCl 2 solutions were evaluated with the use of murine fibroblasts L929 and human osteosarcoma cell line U-2 OS. The microstructure of the Zn alloys consisted of recrystallized Zn grains of 1202μm in size and fine Mg 2 Zn 11 particles arranged parallel to the hot extrusion direction. Mechanical tests revealed that the hardness and strength increased with increasing Mg concentration. The Zn–0.8 Mg alloys showed the best combination of tensile mechanical properties (tensile yield strength of 20302MPa, ultimate tensile strength of 30102MPa and elongation of 15%). At higher Mg concentrations the plasticity of Zn–Mg alloys was deteriorated. Cytotoxicity tests with alloy extracts and ZnCl 2 solutions proved the maximum safe Zn 202+ concentrations of 12002μM and 8002μM for the U-2 OS and L929 cell lines, respectively. Ames test with extracts of alloys indicated that the extracts were not mutagenic. The comet assay demonstrated that 1-day extracts of alloys were not genotoxic for U-2 OS and L929 cell lines after 1-day incubation.

|

| [18] |

Scientific Reports 5 : Article number: 10719 10.1038/srep10719 ; published online: 29 May 2015 ; updated: 05 August 2015 .

|

| [19] |

Apart from the industrial and automotive applications, Zn and Zn-based alloys are considered as a new kind of potential biodegradable material quite recently. However, one drawback of pure Zn as potential biodegradable metal lies in that pure Zn has quite low strength and plasticity. In the present study, three important IIA essential nutrient elements Mg, Ca and Sr and hot-rolling and hot-extrusion thermal deformations have been applied to overcome the drawback of pure Zn and benefit the biocompatibility of Zn-based potential implants. The microstructure, mechanical properties, corrosion behavior, hemocompatibility, in vitro cytocompatibility were studied systematically to investigate their feasibility as bioabsorbable implants. The results showed that the mechanical properties of the ternary Zn–1Mg–1Ca, Zn–1Mg–1Sr and Zn–1Ca–1Sr alloys are much higher than that of pure Zn, owing to both the alloying effects and thermal deformation effects. In vitro hemolytic rate test and cell viability test indicated that the addition of the IIA nutrient alloying elements Mg, Ca and Sr into Zn can benefit their hemocompatibility and cytocompatibility, which would further guarantee the biosafety of these new kind of biodegradable Zn-based implants for future clinical applications.

|

| [20] |

The upper reaches of the Heihe River have been regarded as a hotspot for phytoecology, climate change, water resources and hydrology studies. Due to the cold-arid climate, high elevation, remote location and poor traffic conditions, few studies focused on heavy metal contamination of soils have been conducted or reported in this region. In the present study, an investigation was performed to provide information regarding the concentration levels, sources, spatial distributions, and environmental risks of heavy metals in this area for the first time. Fifty-six surface soil samples collected from the study area were analyzed for Cr, Mn, Ni, Cu, Zn, As, Cd and Pb concentrations, as well as TOC levels. Basic statistics, concentration comparisons, correlation coefficient analysis and multivariate analyses coupled with spatial distributions were utilized to delineate the features and the sources of different heavy metals. Risk assessments, including geoaccumulation index, enrichment factor and potential ecological risk index, were also performed. The results indicate that the concentrations of heavy metals have been increasing since the 1990s. The mean values of each metal are all above the average background values in the Qinghai Province, Tibet, China and the world, except for that of Cr. Of special note is the concentration of Cd, which is extremely elevated compared with all background values. The distinguished ore-forming conditions and well-preserved, widely distributed limestones likely contribute to the high Cd concentration. Heavy metals in surface soils in the study area are primarily inherited from parent materials. Nonetheless, anthropogenic activities may have accelerated the process of weathering. Cd presents a high background concentration level and poses a severe environmental risk throughout the whole region. Soils in Yinda, Reshui daban, Kekeli and Zamasheng in particular pose threats to the health of the local population, as well as that of livestock and wildlife.

|

| [21] |

The microstructure, mechanical properties, in vitro degradation behavior and hemocompatibility of novel Zn–1Mg–0.1Sr and Zn–1Mg–0.5Sr (wt%) ternary alloys were evaluated with pure Zn as control. The results indicated that Zn–Mg–Sr alloys exhibited much higher yield strength (YS), ultimate tensile strength (UTS), hardness and corrosion rate than those of pure Zn. But their elongation and hemolysis rates were reduced. Furthermore, the hot-rolled Zn–1Mg–0.1Sr alloy presented the superior mechanics performance (196.84±13.2002MPa, 300.08±6.0902MPa, 22.49±2.52%, 104.31±10.18 for YS, UTS, Elongation and hardness, respectively), appropriate corrosion rate (0.15±0.0502mm/year) and excellent hemocompatibility (hematolysis rate of 1.10±0.2% and no signs of thrombogenicity), showing a preferable candidate as the biodegradable implant material.

|

| [22] |

In this paper the influence of copper and magnesium content in the microstructural evolution during the solidification of Zn–402wt.% Al hypoeutectic alloys was investigated using the CA-CCA method (Computer-Aided Cooling Curve Analysis) and SEM (Scanning Electron Microscopy). The identification of chemical composition of the phases and microconstituents was done by SEM using the EDS (Energy Dispersive X-Ray Spectroscopy) operation mode. For that purpose, ternary and quaternary alloys were prepared with different amounts of copper and magnesium. The influence of both copper and magnesium amounts on the transformation temperatures of the Zn–Al based hypoeutectic alloys was evident in the distinct microstructures formed during solidification as well as in the cooling curves obtained by thermal analyses, promoting modifications in solid–liquid temperature range, in the kinetic and also in the chemical compositions of the phase transformation. The addition of extra copper promoted the formation of significant quantities of the copper-rich phase (CuZn 4 precipitate) in the interdendritic region, while the addition of extra magnesium promoted the formation of the magnesium-rich phase and changed not only the morphology of the primary dendrites but also its relative content. Besides, an increase in the relative primary eutectic structure and a decrease in the quantity of the lamellae eutectoid structure were observed. Additionally, the secondary lamellar eutectic became more refined in the presence of higher magnesium content. All the cooling curves are in agreement with the observed microstructure. Both elements, copper and magnesium, also promoted an increase in the hardness of the Zn–4Al hypoeutectic alloys due to the formation of CuZn 4 phase and to the secondary lamellae eutectic refinement, respectively.

|

| [23] |

A two-phase zinc–aluminum alloy (Zn–802wt.% Al) has been subjected to severe plastic deformation via equal channel angular extrusion (ECAE). The alloy was successfully extruded at homologous temperatures around 0.5 T m through various strain paths and magnitudes. Multi-pass ECAE processing following different routes led to the elimination of the as-cast dendritic microstructure and formed a structure of elongated, ribbon-shaped phases. Monotonic tensile tests were conducted at room temperature along the longitudinal axis of the ECAE samples in addition to the directions parallel and perpendicular to the long axis of the elongated hard eutectoid phase particles in order to reveal the effect of microstuctural morphology on the anisotropic flow response. The flow strength levels increased significantly after the first ECAE pass, and then saturated at a slightly higher value after the subsequent passes in route B C . An average increase of about 50% in ultimate tensile strength and about 100 times increase in elongation to failure were achieved after eight ECAE passes following route B C , as compared to the as-cast values. Despite the relative chemical homogenization between the hard and soft phases, the size and distribution of the hard phase in the matrix are found to be the dominant factor controlling the flow response of the present two-phase zinc–aluminum alloy after ECAE. The hard phase size, morphology, and distribution were also found to control the anisotropy in the flow strength and elongation to failure of the ECAE processed samples. Notable flow softening with increasing number of ECAE passes, a general observation for the ECAE processed Zn–Al alloys with Al content more than 12%, was lacking in the present alloy which was attributed to the hardening effect of the fine eutectoid particles in the eutectic matrix overcoming the softening effect of deformation-induced chemical homogenization.

|

| [24] |

Tensile properties and impact toughness of the severe plastically deformed Zn–40Al alloy were investigated. The material billets were subjected to equal-channel angular extrusion (ECAE). After processing, elongation to failure increased significantly with the increasing number of ECAE passes. ECAE also increased the strength levels after one pass, however, they were reduced with the higher number of passes. The observed softening of the alloy upon multiple ECAE passes was shown to be due to the deformation-induced homogenization and the continuous change in the composition of the constituting phases with the number of passes. In addition, the volume fraction of the hard phase decreased due to dissolution and/or breakage. The impact toughness of the alloy was improved by multi-pass ECAE due to the significant increase in ductility. These findings demonstrate that multi-pass ECAE effectively transforms brittle Zn–Al cast alloys into tougher materials with ductile fracture behavior.

|

| [25] |

We study the effects of dilute Mg addition on the microstructure formation and mechanical properties of a ZnAl4Cu1 alloy. On the basis of the composition of the commercial alloy Z410 (402wt% Al, 102wt% Cu, and 0.0402wt% Mg), three laboratory alloys with different Mg contents (0.0402wt%, 0.2102wt% and 0.3102wt%) are characterised in terms of their mechanical properties and microstructures using ex-situ and in-situ tensile tests in conjunction with scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and electron backscatter diffraction (EBSD). Increasing Mg content causes the precipitation of Mg 2 Zn 11 phase precipitates and refined lamellar spacings in the eutectoid phase. The alloy with a medium Mg content (0.2102wt%) exhibits the highest yield strength both at room temperature and at elevated temperatures. Further, we show that dilute Mg alloying causes an improvement of the ductility of ZnAl4Cu1 base-alloys, especially at elevated temperatures. In addition, the alloys reveal two distinct deformation regimes distinguishable close to room temperature and at commonly employed strain rates, with work hardening and brittle fracture exhibited at room temperature and/or elevated strain rate (5×10 614 02s 61 1 ), and work softening and ductile fracture at elevated temperature and/or low strain rate (6×10 616 02s 611 ). The deformation mechanisms and fracture behaviour in both regimes are investigated and the underlying physical mechanisms of the observed phenomena are discussed.

|

| [26] |

[Cited within:1]

|

| [27] |

Multi-pass equal-channel angular pressing (ECAP) was applied to a commercially used zinc–aluminum alloy (ZA-12) at a temperature of about 7502°C by using route B c , where the sample is rotated by 90° along its longitudinal axis between adjacent passes. The strength, hardness and ductility of the alloy processed by ECAP were investigated as a function of number of passes. In addition, variations in the applied load during pressing through the die were analyzed and the relationship between maximum pressing load and strength of the alloy was established. It was observed that the mechanical properties (mainly strength and ductility) were improved after ECAP processing. It was also observed that the tensile strength and the maximum pressing load showed similar trends with number of passes. The improvement in mechanical properties is mainly attributed to both refined microstructure and high density of dislocations that may occur during ECAP. Since this method of severe plastic deformation leads to an increase in both strength and ductility even after a single pass through the die, it is concluded that ECAP provides a simple and effective processing procedure for improving the mechanical properties of Zn–Al alloys. With these improved properties, Zn–Al alloys can be potentially used in new engineering applications.

|

| [28] |

[Cited within:1]

|

| [29] |

Abstract Coronary heart disease is a major health problem in developed countries. Many studies have shown that elevated serum concentrations of total or low-density-lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL cholesterol) are high risk factors, whereas high concentrations of high-density-lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL cholesterol) or a low LDL to HDL cholesterol ratio may protect against coronary heart disease. Plant sterols and stanols derived from vegetable oils or wood pulp have been shown to lower total and LDL cholesterol levels in humans by inhibiting cholesterol absorption from the intestine. These findings may lead to new therapeutic options to treat hypercholesterolemia. In addition, phytosterols may influence cell growth and apoptosis of tumor cells. However, they can interfere with the absorption of fat soluble vitamins and carotenoids.

|

| [30] |

URL

[Cited within:1]

|

| [31] |

[Cited within:2]

|

| [32] |

In this review, our basic and most recent understanding of copper biochemistry and molecular biology for mammals (including humans) is described. Information is provided on the nutritional biochemistry of copper, including food sources, intestinal absorption, transport, tissue distribution, and excretion, along with descriptions of copper binding proteins and other factors involved and their roles in these processes. The metabolism of copper and its importance for the functions of a roster of vital enzymes is detailed. Its potential toxicology is also addressed. Alterations in copper metabolism associated with genetic and nongenetic diseases are summarized, including potential connections to inflammation, cancer, atherosclerosis, and anemia, and the effects of genetic copper deficiency (Menkes syndrome) and copper overload (Wilson disease). Understanding these diseases suggests new ways of viewing the normal functions of copper and provides new insights into the details of copper transport and distribution in mammals.

|

| [33] |

Vitamin K (as phylloquinone and menaquinones) is an essential cofactor for the conversion of peptide-bound glutamate to 纬-carboxy glutamic acid (Gla) residues in a number of specialized Gla-containing proteins. The only unequivocal deficiency outcome is a bleeding syndrome caused by an inability to synthesize active coagulation factors II, VII, IX, and X, although there is growing evidence for roles for vitamin K in bone and vascular health. An adult daily intake of about 100 渭g of phylloquinone is recommended for the maintenance of hemostasis. Traditional coagulation tests for assessing vitamin K status are nonspecific and insensitive. Better tests include measurements of circulating vitamin K and inactive proteins such as undercarboxylated forms of factor II and osteocalcin to assess tissue and functional status, respectively. Common risk factors for vitamin K deficiency in the hospitalized patient include inadequate dietary intakes, malabsorption syndromes (especially owing to cholestatic liver disease), antibiotic therapy, and renal insufficiency. Pregnant women and their newborns present a special risk category because of poor placental transport and low concentrations of vitamin K in breast milk. Since 2000, the Food and Drug Administration has mandated that adult parenteral preparations should provide a supplemental amount of 150 渭g phylloquinone per day in addition to that present naturally, in variable amounts, in the lipid emulsion. Although this supplemental daily amount is probably beneficial in preventing vitamin K deficiency, it may be excessive for patients taking vitamin K antagonists, such as warfarin, and jeopardize their anticoagulant control. Natural forms of vitamin K have no proven toxicity.

|

| [34] |

[Cited within:1]

|

| [35] |

Controversy exists over whether aluminium has a role in the aetiology of Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimer's disease is neuropathologically characterized by the occurrence of a minimum density of neurofibrillary tangles and neuritic plaques in the hippocampus and the association cortex of the brain. The purported association of aluminium with Alzheimer's disease is based on: (1) the experimental induction of fibrillary changes in the neurons of animals by the injection of aluminium salts into brain tissue; (2) reported detection of aluminium in neuritic plaques and tangle-bearing neurons; (3) epidemiological studies linking aluminium levels in the environment, notably water supplies, with an increased prevalence of dementia; and (4) a reported decrease in the rate of disease progression following the administration of desferroxamine, an aluminium chelator, to clinically diagnosed sufferers of Alzheimer's disease. Here we use nuclear microscopy, a new analytical technique involving million-volt nuclear particles, to identify and analyse plaques in postmortem tissue from patients with Alzheimer's disease without using chemical staining techniques and fail to demonstrate the presence of aluminium in plaque cores in untreated tissue.

|

| [36] |

Magnesium (Mg) and its alloys have been intensively studied as biodegradable implant materials, where their mechanical properties make them attractive candidates for orthopaedic applications. There are several commonly used in vitro tests, from simple mass loss experiments to more complex electrochemical methods, which provide information on the biocorrosion rates and mechanisms. The various methods each have their own unique benefits and limitations. Inappropriate test setup or interpretation of in vitro results creates the potential for flawed justification of subsequent in vivo experiments. It is therefore crucial to fully understand the correct usages of each experiment and the factors that need to be considered before drawing conclusions. This paper aims to elucidate the main benefits and limitations for each of the major in vitro methodologies that are used in examining the biodegradation behaviour of Mg and its alloys. (c) 2011 Acta Materialia Inc. Published by Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

|

| [37] |

[Cited within:1]

|

| [38] |

High strain rate superplasticity; Zn-Al alloys; Ultrafine-grained; microstructure; zn-22-percent al-alloy; deformation-behavior; eutectoid alloy; seismic; damper; microstructure; microscopy; mechanism; evolution; metals; flow

|

| [39] |

The effect of rare earth metal (Gd, Dy, Er, and Y) small additions on the corrosion behaviour of Zn–5% Al (Galfan) alloy has been investigated. The corrosion resistance of Zn–5Al–0.1Gd, Zn–5Al–0.1Dy, Zn–5Al–0.1Er, and Zn–5Al–0.1Y alloys has been assessed by electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) measurements carried out in a 0.102M NaCl solution, at approximately neutral pH, without stirring and in contact with the air. For comparison, the electrochemical tests have also been carried out on the Galfan alloy. EIS results showed that rare earths’ addition significantly improves the corrosion behaviour of Galfan. This improvement is most likely due to enhanced barrier properties of the corrosion products layer and additional active corrosion protection originated from the inhibiting action of the lanthanide ions entrapped as oxides/hydroxides in this surface layer.

|

| [40] |

[Cited within:1]

|

| [41] |

Abstract Marine organisms are rich sources of structurally diverse bioactive nitrogenous components. In recent years, numerous bioactive peptides have been identified in a range of marine protein resources, such as antioxidant peptides. Many studies have approved that marine antioxidant peptides have a positive effect on human health and the food industry. Antioxidant activity of peptides can be attributed to free radicals scavenging, inhibition of lipid peroxidation, and metal ion chelating. Moreover, it has also been verified that peptide structure and its amino acid sequence can mainly affect its antioxidant properties. The aim of this review is to summarize kinds of antioxidant peptides from various marine resources. Additionally, the relationship between structure and antioxidant activities of peptides is discussed in this paper. Finally, current technologies used in the preparation, purification, and evaluation of marine-derived antioxidant peptides are also reviewed.

|

| [42] |

The influence of aluminium content on the corrosion behaviour of superplastic Zinc–Aluminium alloys immersed in simulated acid rain was investigated. ZA4, ZA8, ZA12, and ZA16 alloys were used for the test. The Al-rich phase was prone to preferential attack when the superplastic Zn–Al alloy was immersed for 502d. However, with increasing ratios of the Al phase, the corrosion rates of the four samples decreased in the order ZA402>02ZA802>02ZA1202>02ZA16. The corrosion rate of the alloy decreased with increasing Al content, which may be related to the distribution of the Al-rich phase. Corrosion kinetic parameters were also calculated.

|

| [43] |

The aim of this experimental investigation is to evaluate the electrochemical behavior of an as-cast Zn-rich Zn鈥揅u peritectic alloy as a function of both the solute macrosegregation profile and the microstructure cellular spacing. A directional solidification apparatus was used to obtain the as-cast samples. Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS), potentiodynamic polarization techniques and an equivalent circuit analysis were used to evaluate the corrosion resistance in a 0.5M NaCl solution at 25掳C. It was found that both copper content and cell spacing are significantly affected by the position along the casting length from the cooled bottom of the casting. These parameters play interdependent roles on the resulting corrosion behavior. Samples which are closer to the casting cooled surface are more affected by the solute inverse segregation, i.e. have a Cu content that is higher than the alloy nominal composition. This is shown to be a driving-force leading to a decrease in the corrosion resistance. However, for other samples with similar Cu content and close to the nominal alloy composition, the cell spacing seems to be the driving-force associated with the corrosion resistance and for these cases finer microstructures are shown to be related to higher corrosion resistance.

|

| [44] |

As reinforcement flax fibre has the potential to replace glass fibre in fibre-reinforced polymer, composite and coir fibre can be used in concrete. To achieve sustainable construction, this study presents an experimental investigation of a flax fibre-reinforced polymer tube as concrete confinement. Results of 24 flax fibre-reinforced polymer tube-confined plain concrete and coir fibre-reinforced concrete cylinders under axial compression are presented. Test results show that both flax fibre-reinforced polymer tube-confined plain concrete and fibre-reinforced concrete offer high axial compressive strength and ductility. A total of 23 existing design- and analysis-oriented models were considered to predict the ultimate axial compressive strength and strain of flax fibre-reinforced polymer tube-confined plain concrete and fibre-reinforced concrete. It was found that a few existing design- and analysis-oriented models predicted the ultimate strengths of all the flax fibre-reinforced polymer tube-confined plain concrete and fibre-reinforced concrete cylinders accurately. However, no strain models considered match the ultimate strains of these specimens. Two new equations are proposed to evaluate the ultimate axial strain of flax fibre-reinforced polymer tube-confined plain concrete and fibre-reinforced concrete.

|

| [45] |

|

| [46] |

The binding of Zn2+ to tubulin and the ability of this cation to promote the polymorphic assembly of the protein were examined. Equilibrium binding showed the existence of more than 60 potential Zn2+ binding sites on the dimer, including a number of high-affinity sites. The number of high-affinity sites, estimated by using a standard amount of phosphocellulose to remove more weakly bound Zn2+, reached a maximum of 6-7.5 with increasing levels of Zn2+ in the incubation solution. The number also increased with time of incubation at a single Zn2+ concentration. It is suggested that tubulin is slowly denatured in the presence of Zn2+, exposing more binding sites. Cu+ and Cd2+ were effective inhibitors of Zn2+ binding; Mg2+, Mn2+, and Co2+ were much less effective, and Ca2+ was without effect. Zn2+ does not replace the tightly bound Mg2+. GTP reduces the amount of Zn2+ binding under equilibrium conditions and the amount bound to high-affinity sites. Zinc-induced protofilament sheets are produced at a Zn2+/tubulin ratio of 5 in the presence of 0.5 mM GTP, conditions where about two to three Zn2+ ions would be bound to the dimer. At higher GTP concentrations, less assembly occurred, and the products were narrower sheets and microtubules. Zn2+-tubulin, isolated from phosphocellulose, will not assemble unless Mg2+ and dimethyl sulfoxide (Me2SO) or more Zn2+ is added. Broad protofilament sheets, formed from Zn2+-tubulin in the presence of Mg2+ and Me2SO, contain slightly more than one Zn2+ per dimer. It is concluded that Zn2+ stimulates tubulin assembly by binding directly to the protein, not via a ZnGTP complex.

|

| [47] |

After ingestion of 220 mg zinc sulfate, platelet aggregation was evaluated at various time intervals (i.e., T = 0, 1, and 3 hr) and the autologous plasma analyzed by atomic absorption analysis. The zinc levels increased maximally some 0.4 +/- 0.2 microgram/ml within 3 hr after ingestion, which for the entire blood pool corresponds to only 5% of the ingested zinc. Aggregation responses of platelet rich plasma (PRP), instigated with suboptimal levels of thrombin (less than 0.2 U/ml), ADP (less than 2 microM), epinephrine (less than 2 microM), collagen (less than 2 micrograms/ml), or PAF (less than 50 ng/ml), show significant improvement to at least one aggregant. Mean +/- SEM values for delta % aggregation increase are as follows: thrombin, 51 +/- 10%; epinephrine, 21 +/- 6%; ADP, 31 +/- 6%; collagen 23 +/- 6%; and platelet aggregating factor (PAF), 56 +/- 6%. For controls, the platelets from one individual with Glanzmann thrombasthenia as well as four undosed volunteers exhibited no significant changes in platelet responsiveness. Increased platelet responsiveness to agonists after zinc sulfate ingestion was observed in PRP from blood collected in either citrate or heparin. We demonstrate that within a relatively short time period, single bolus of nutritional zinc intake can significantly increase platelet reactivity. These findings show that nutritional zinc availability is relevant to hemostasis and may pertain to the viability of platelet concentrates in blood banks.

|

| [48] |

Background: To avoid the inherent disadvantages of copper-containing intrauterine device (Cu-IUD) induced by free Cu2+, two other well-perforrning metal ions, namely, Ag+, with long-effective antimicrobial properties, and Zn2+, as an essential trace element, are being considered for use in the future as multifunctional IUDs. The purpose of this study was to assess the cytotoxicity of these metal ions and their mixtures on primary human endometrial epithelial cells (HEECs) cultured in vitro and to provide several choices of alternative potential materials for creating excellent IUDs in the future.<br/>Study Design: With the use of 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide-formazan (MTT-f) production, the cytotoxic effects of single metal ions (Cu2+, Zn2+, Ag+) on HEECs after exposure for 24, 48 or 72 h were investigated, and the synergistic and antagonistic effects of two ions applied simultaneously were also assessed.<br/>Results: The cytotoxicity of the metal ions on HEECs ranked as follows: Ag+>Cu2+>Zn2+. All combinations of those tested indicated that the Cu2++Zn2+ system exhibited an antagonistic effect absolutely, the Zn2++Ag+ system showed both antagonism and slight synergism, and asynergistic effect was observed in the Cu2++Ag+ system.<br/>Conclusion: From a perspective of favorable biocompatibility, Zn2+ and the Cu2++Zn2+ mixture showed evidence of potential components for use in future IUDs. Although having strong cytotoxicity, Ag+ with its low release rate and broad-spectrum antibiotic activity may also be considered. The study also demonstrated the relative stability of Cu2+ as a classic material of IUD. (C) 2012 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

|

| [49] |

The recent proposal of using Zn-based alloys for biodegradable implants was not supported with sufficient toxicity data. This work, for the first time, presents a thorough cytotoxicity evaluation of Zn-3Mg alloy for biodegradable bone implants. Normal osteoblast cells were exposed to the alloy's extract and three main cell-material interaction parameters: cell health, functionality and , were evaluated. Results showed that at the concentration of 0.75mg/ml alloy extract, cell viability was reduced by ~50% through an at day 1; however, cells were able to recover at days 3 and 7. Cytoskeletal changes were observed but without any significant DNA damage. The downregulation of protein levels did not significantly affect the mineralization process of the cells. Significant differences of and inflammatory biomarkers were noticed, but not interleukin 1-beta, indicating that the cells underwent a healing process after exposure to the alloy. Detailed analysis on the cell-material interaction is further discussed in this paper.

|

| [50] |

We present a new approach for the fabrication of magnetic thermoresponsive polymer microcapsules with mobile magnetic spherical cores. The microcontainers form fried-egg-like structures with a polymer shell layer of 50聽nm due to the existence of hollow cavities. The microcontainers undergo a temperature-induced volume phase transition upon changing the temperature and present an impressive magnetic response. The magnetic saturation of these smart microcontainers (42聽emu/g) is high enough to meet most requirements of bioapplications. To further investigate the potential application of these smart microcontainers in biotechnology, Candida rugosa lipase was selected for the enzyme immobilization process. The immobilized lipase exhibited excellent thermal stability and reusability in comparison with the free enzyme. The adsorption/release of the lipase from the microcontainers can be controlled by the environmental temperature and magnetic force, thus, offering new potential applications such as in controlled drug delivery, bioseparation, and catalysis.

|

| [51] |

We have investigated the use of the viability index of the cells of the human embryo鈥檚 kidney of the NEK 293 line as a biomarker when assessing water toxicity before and after purification of Cu 2+ and Zn 2+ . Addition to the incubation medium of the aqueous solution of copper sulfate results in a substantial decrease of the culture viability. An increase of the Zn 2+ concentration does not produce any toxic effect on HEK 293 and HUVEC cells being cultivated. In the case of simultaneous introduction of ions of copper and zinc to the incubation medium the toxic effect of Cu 2+ on the HEK 293 cells is absent while on endotheliocytes HUVEC persists. The procedure of water purification of ions of heavy metals was run concurrently with the use of synthetic and natural sorbents. The assessment on the HEK 293 cells of water toxicity after purification demonstrated high efficiency and safety of the composite material with active polysaccharide component.

|

| [52] |

To evaluate the anticancer mechanism of the new complex-Λ-WH0402 at the cellular level, the in vitro cytotoxicity of Λ-WH0402 was investigated on 10 lines. Λ-WH0402 was found to have higher anticancer activity than toward HCCLM6 that have high metastatic characteristics. Meanwhile, Λ-WH0402 showed an antimetastatic effect on HCCLM6 in vitro, mostly through its effect on , invasion and migration. In addition, Λ-WH0402 significantly reduced to the lungs in orthotopic () models induced by HCCLM6 . Furthermore, Λ-WH0402 exerted an inhibitory effect on and proliferation and induced dose-dependent in the S phase in HCCLM6 . Immunoblotting analysis showed that Λ-WH0402 not only decreased the expression of antiapoptotic and (), but also significantly increased the expression of in HCCLM6 . More importantly, we identified that Λ-WH0402 treatment reduced the interaction between and , and increased the expression of autophagic activation marker LC3B-II in HCCLM6 . On the whole, our results suggested that the anitcancer activity of Λ-WH0402 is mediated through promoting the -dependent pathway in HCCLM6 .

|

| [53] |

Pre-harvest sprouting (PHS) in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) occurs when physiologically mature kernels begin germinating in the spike. The objective of this study was to provide fundamental information on physicochemical changes of starch due to PHS in Hard Red Spring (HRS) and Hard White Spring (HWS) wheat. The mean values of 伪-amylase activity of non-sprouted and sprouted wheat samples were 0.12 CU/g and 2.00 CU/g, respectively. Sprouted samples exhibited very low peak and final viscosities compared to non-sprouted wheat samples. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images showed that starch granules in sprouted samples were partially hydrolyzed. Based on High Performance Size Exclusion Chromatography (HPSEC) profiles, the starch from sprouted samples had relatively lower molecular weight than that of non-sprouted samples. Overall, high 伪-amylase activity caused changes to the physicochemical properties of the PHS damaged wheat.

|

| [54] |

The purpose of the study was to condense existing scientific evidence about the relation between aluminum (Al) exposure and risk for the development of Alzheimer's Disease (AD), evaluating its long-term effects on the population's health. A systematic literature review was carried out in two databases, MEDLINE and LILACS, between 1990 and 2005, using the uniterms: "Aluminum exposure and Alzheimer Disease" and "Aluminum and risk for Alzheimer Disease". After application of the Relevance Test, 34 studies were selected, among which 68% established a relation between Al and AD, 23.5% were inconclusive and 8.5% did not establish a relation between Al and AD. Results showed that Al is associated to several neurophysiologic processes that are responsible for the characteristic degeneration of AD. In spite of existing polemics all over the world about the role of Al as a risk factor for AD, in recent years, scientific evidence has demonstrated that Al is associated with the development of AD.

|

| [55] |

Previous uncertainty regarding glomerular ultrafilterability (UF) of aluminum has limited the definition of renal Al handling. Glomerular micropuncture was therefore performed in hydropenic Munich-Wistar rats infused with AlCl3 to achieve plasma (P) Al levels between 2 and 10 mg/liter. Glomerular fluid, P, and urine Al concentrations were measured by flameless atomic-absorption spectrophotometry. UFA1 was inversely correlated with PA1 [%UFA1 = 10.3 - 8.4 (log PA1), r = -0.90, P less than 0.01]. When this equation was used to calculate the filtered load (FLA1), A1 excretion (UA1V, ng/min) in simultaneously collected samples was found to be a direct function of FLA1 [UA1V = 5.7 + 0.37 (FLA1), r = 0.93, P less than 0.01]. Fractional excretion (FE) of A1 was 39.4 +/- 4.2% in these hydropenic experiments (FENa = 0.3 +/- 0.1%). We next evaluated the tubular handling of A1 (using these UF data) during step-wise extracellular fluid volume expansion with isotonic saline (2.5, 5.0, 7.0, and 7.0% body wt) and during the infusion of increasing doses (2.7, 5.3, 8.0, and 8.0 mg X kg-1 X h-1) of furosemide as urinary losses were quantitatively replaced. The natriuresis produced by volume expansion (FENa = 1.0, 3.0, 8.4, and 7.9%) and furosemide (FENa = 4.2, 6.0, 6.6, and 6.7%) were comparable. At similar FLA1, 7% volume expansion but not furosemide (at any dose) increased UA1V (240 and 95 ng/min, respectively, vs. 116 ng/min in hydropenia) and FEA1 (84.5 and 29.4 vs. 37.4%, respectively). These data indicate that at pharmacological PA1 levels, less than 8.4% of PA1 is ultrafilterable, suggesting extensive plasma protein binding.(ABSTRACT TRUNCATED AT 250 WORDS)

|

| [56] |

[Cited within:1]

|

| [57] |

Vertically aligned ZnO nanowires (NWs) hybridized with reduced graphene oxide sheets (rGO) were applied in efficient visible light photoinactivation of bacteria. To incorporate graphene oxide (GO) sheets within the NWs two different methods of drop-casting and electrophoretic deposition (EPD) were utilized. The EPD method yielded effective penetration of the positively charged GO sheets into the NWs to form a spider net-like structure, whereas the drop-casting method resulted in only a surface coverage of the GO sheets on top of the NWs. The electrical connection between the EPD-incorporated sheets and the NWs was checked by monitoring the electron transfer from UV-assisted photoexcited ZnO NWs into the GO sheets, during photocatalytic reduction of the sheets. The obtained rGO/ZnO composites were applied in visible light photoinactivation of Escherichia coli bacteria. The ZnO NWs could inactivate only 6558% of the bacteria, while both drop-casting and EPD-prepared GO/ZnO composites exhibited strong antibacterial activities (especially the EPD sample with 6599.5% photoinactivation), under visible light irradiation for 1h. In fact, the visible light photocatalytic activity of the EPD-prepared GO/ZnO NW composite was found 651.9 and 6.2 folds of the activity of the GO/ZnO composite prepared by drop-casting method and the bare ZnO NWs.

|

| [58] |