Calcium sulfate whiskers (CSWs) modified with glutaraldehyde-crosslinked poly(vinyl alcohol) (PVA) or traditional surface modifiers, including silane coupling agent, titanate coupling agent and stearic acid, were used to strengthen poly(vinyl chloride) (PVC), and the morphologies, mechanical and heat resistant properties of the resulting composites were compared. The results clearly show that glutaraldehyde cross-linked PVA modified CSW/PVC composite (cPVA@CSW/PVC) has the strongest interfacial interaction, good and stable mechanical and heat resistant properties. Nielsen's modified Kerner's equation for Young's modulus is better than other models examined for the CSW/PVC composites. The half debonding angle

Poly(vinyl chloride) (PVC) is one of the most commercially important polymers with a wide range of applications, such as pipes, electric cables and films[1]. The properties (e.g. stiffness, gas permeability, heat resistance, etc.) of PVC can be significantly improved by using appropriate fillers or reinforcing agents[2]. Calcium sulfate whisker (CSW) is a fiber-shaped single crystal with many desirable properties, such as high strength, high stiffness and low cost[3], making it an excellent filler for polymer matrix composites. However, despite the advantages of the incorporation of fillers into PVC[4,5], it can lead to a reduction in the mechanical properties of the composites due to incompatibility between the fillers and polymers[6,7]. The surface of fillers can be modified to improve their wettability and adhesion with the polymer matrix[8], and the commonly used surface modifiers include silane coupling agents[9,10], titanate coupling agents[11] and fatty acids[12].

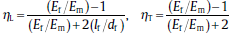

Several semi-empirical models have been proposed to quantitatively characterize the interfacial adhesion between particles and matrix in particulate-filled polymer composites[13]. A new parameter, half debonding angle

We have previously reported an effective surface modification method for CSW based on the cross-linking reaction of poly(vinyl alcohol) (PVA) to cladding to the whisker surface[18]. The main purpose of this study is to compare the morphologies, mechanical and heat resistant properties of CSW/PVC composites modified by our method and traditional surface modification method. The theoretical models for Young's modulus of composites were applied to these CSW/PVC composites, and the half debonding angle was calculated from the tensile strength to quantitatively characterize the effect of surface treatments on the interfacial adhesion between CSW and PVC matrix.

PVC (SG-5) was purchased from Dongguan Dansheng Plastic Materials Co., Ltd. (Dongguan, China); CSWs were purchased from Shanghai Fengzhu Trading Co., Ltd (Shanghai, China); organic tin, dioctyl phthalate (DOP), glyceryl monostearate (GMS), acrylic processing aid (ACR), paraffin wax, silane coupling agent (KH-550) and titanate coupling agent (NDZ-201) were commercially available, all of which were of industrial grade; stearic acid was purchased from Shanghai Lingfeng Reagent Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China); and PVA (PVA1750) and glutaraldehyde solution were purchased from Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). The purities of these materials are listed in

2.2.1. Preparation of modified CSWs

CSWs modified by silane coupling agents (Si-CSW) were prepared as follows: 1.5 g of KH550 was pre-hydrolyzed in 95 wt% ethanol solution and 50 g of dried CSWs was added sequentially into a 500 mL three-necked round-bottom flask fitted with a mechanical overhead stirrer, and then ammonia was added until the pH reached 9. The mixture was stirred at 75 °C for 4 h, and then the obtained products were dried under vacuum at 100 °C for 2 h to remove excess water.

CSWs modified by titanate coupling agent (Ti-CSW) or stearic acid (SA-CSW) were prepared by a similar procedure, except that pH adjustment was not required.

cPVA@CSWs were prepared as described in our previous study[18]: PVA aqueous solution and dried CSW were added sequentially into a three-necked round-bottom flask. Then, the glutaraldehyde solution (cross-linking agent) and sulfuric acid solution (pH adjuster) were added, and the mixture was stirred at room temperature for 1 h. The obtained products were dried under vacuum at 80 °C for 2 h to complete the cross-linking reaction and remove excess water.

2.2.2. Preparation of the composites

The composites were prepared as described in our previous study[18]: PVC resin (100 phr) was mixed with various contents of CSW or modified CSW using organic tin (2 phr) as the heat stabilizer and DOP (4 phr) as the plasticizer. GMS (0.6 phr), ACR (4 phr) and paraffin wax (0.4 phr) were then added. All PVC constitutes were mixed uniformly and processed using a two-roll mill at 170 °C. At last, the resultant compound was molded into rectangular sheets by compression molding at 170 °C and 10 MPa for 5 min using a plate vulcanizing press.

2.3.1. Characterization of modified CSWs

The activation indexes of CSWs were determined as follows: 5.00 g of CSW and 200 mL of deionized water were added sequentially into a separatory funnel and shaken at 120 times/min for 1 min. Then the mixture was allowed to stand for 10 min, and the settling whiskers removed from the mixture were dried and weighed. The activation index was calculated using the formula bellow:

ω=(1-m/m0)×100%

where

The surface morphologies of modified CSWs were observed by scanning electron microscopy (SEM, S-3400N, Hitachi, Japan). The whiskers were coated with a thin gold layer before testing.

2.3.2. Mechanical properties

The tensile properties were determined on an MTS E44 universal testing machine in accordance with ISO 527, and the notched impact strength was determined on a CEAST 9050 tester according to ISO 179. The means and standard deviations were calculated from at least five independent tests for each sample.

2.3.3. Morphologies of the composites

The tensile fracture surfaces of the composites were characterized by SEM (S-4800, Hitachi, Japan). Prior to SEM observation, the fracture surfaces were coated with a thin gold layer.

2.3.4. Heat resistance properties

Vicat softening temperatures (VST) were measured under a load of 10 N at a heating rate of 120 °C/h using a VST tester (ZWK1302-B, MTS, China) according to ISO 306: 2004.

The activation indexes of modified CSWs are listed in

Fig. 1 shows the surface morphologies of different modified CSWs. The diameters of modified whiskers are decreased to varying degrees as compared with that of unmodified whiskers. Si-CSW has relatively fewer fractured whiskers. The surface of cPVA@CSW is much rougher than that of other whiskers and there are many whiskers with a high aspect ratio. Although there are some small whiskers, they are all coated with cPVA and have strong interfacial interaction with the PVC matrix. In general, their combination has a favorable effect on the performance of the composite. Ti-CSW and SA-CSW have more fractured whiskers, resulting in a decrease in the mechanical properties.

Fig. 2 shows that the Young's modulus of the composites increases with increasing whisker content, resulting in an increase in the stiffness of the composites. However, it is important to note that the tensile strength decreases with increasing whisker content, because the increase in whisker content may lead to poor dispersion and significant agglomeration of CSWs in the PVC matrix and thus weak interfacial adhesion between whiskers and matrix. As a consequence, the load bearing capacity of the cross-sectional area of the composites decreases, and only a small amount of stress could be transferred from the matrix to the whisker surface. In this case, agglomerated whiskers can easily debond from the matrix and thus could not bear any fraction of external load, resulting in a decrease in tensile strength[19]. A similar phenomenon was also reported for many other polymer based composites[19], [20,21].

Fig. 2. (a) Tensile strength and (b) Young's modulus of the composites with different CSW contents.

Si-CSW/PVC, Ti-CSW/PVC, SA-CSW/PVC and cPVA@CSW/PVC composites with different CSW contents were prepared to compare the reinforcing effects of our method and traditional surface modification. In general, cPVA@CSW/PVC composite performs best, especially at a low whisker content. The mechanical performance of Si-CSW/PVC, Ti-CSW/PVC, and SA-CSW/PVC composites is poorer and fluctuates significantly, and the tensile strength and Young's modulus of the composites with 5 wt% CSWs are lower than those of unmodified CSW/PVC composite. However, the mechanical properties of cPVA@CSW/PVC composite are significantly improved[18]. This is because traditional methods are mainly conducted under vigorous stirring and high temperatures, leading to defects on the whisker surface; while our method is simpler and more environmentally friendly, and thus can be a better choice for the modification of fillers.

Fig. 3 shows the Izod impact strengths of CSW/PVC, Si-CSW/PVC, Ti-CSW/PVC, SA-CSW/PVC and cPVA@CSW/PVC composites with different CSW contents. The impact strength is increased from 4.71 kJ m-2 for pure PVC to 6.67 kJ m-2 for CSW/PVC, and further to 11.61 kJ m-2 for cPVA@CSW/PVC with 5 wt% CSWs. The impact strength of other modified CSW/PVC composites is also improved as compared with that of unmodified CSW/PVC. Therefore, the impact property of PVC can be improved by modified CSWs, especially cPVA@CSW. The impact strength increases with the increase of whisker content from 5 to 30 wt%, indicating that CSW acts as a toughness filler for the PVC matrix and can significantly improve the toughness of the composites. Zhang et al.[22] also showed that the impact strength of TiO2/PVC composite increased with TiO2 content up to 40 phr.

The toughening mechanism of CSWs can be described as follows[23]. It is known that the polymer matrix tends to develop cracks along or through the whiskers under the impact force. In the former case, the crack propagation path is increased and thus more energy is consumed; while in the latter case, more energy is also consumed due to the much higher intensity of the whiskers than the matrix, thus contributing to improving the impact strength of the composites. In the case of a large angle between the crack and the whisker orientation, the matrix tends to yield and the whiskers tend to debond from the matrix, consuming part of the energy and thus improving the toughness of the composites. The interfacial interaction of cPVA@CSW/PVC composite is stronger than that of unmodified CSW/PVC composites, and thus more energy is consumed during crack propagation or the pulling out of whiskers, which contributes to the improvement of the impact strength.

The dispersion state of CSWs in the polymer matrix is critical for the mechanical properties of the composites.

Fig. 4. SEM images of the tensile fracture surfaces for the composites with 5 wt% whisker (a1 - CSW/PVC; b1 - cPVA@CSW/PVC; c1 - Si-CSW/PVC; d1 - Ti-CSW/PVC; e1 - SA-CSW/PVC) and the composites with 10 wt% whisker (a2 - CSW/PVC; b2 - cPVA@CSW/PVC; c2 - Si-CSW/PVC; d2 - Ti-CSW/PVC; e2 - SA-CSW/PVC).

The differences in the interfacial adhesion and interaction between CSW and the matrix can be more clearly demonstrated in the composites with a high CSW content.

Fig. 5. SEM images of the tensile fracture surfaces for the composites with 30 wt% whisker. (a1, a2) - CSW/PVC; (b1, b2) - cPVA@CSW/PVC; (c1, c2) - Si-CSW/PVC; (d1, d2) - Ti-CSW/PVC; (e1, e2) - SA-CSW/PVC.

The mechanism of each treatment is shown in

VST reflects the moving ability of the chain segments. The more difficult it is for the chain segments to move, the higher the VST will be[25].

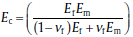

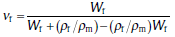

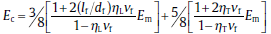

The increase in Young's modulus of the composites reinforced by rigid inorganic fillers can be described by the iso-stress rule of mixtures:

where

where

In this study,

where

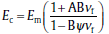

Fig. 8. Young’s modulus of the CSW/PVC composites as a function of filler volume content and its theoretical predictions using different models.

The reduced concentration term is defined as[33]:

The Poisson's ratio of the matrix is taken to be 0.4,

The best fit is obtained when

The discrepancy between the rule of mixture and Nielsen's modified Kerner's equation arises as the former does not consider the filler geometry; whereas the latter considers not only individual filler effect rather than the iso-stress conditions, which is more appropriate for laminates, but also the particle size distribution through the maximum packing fractions.

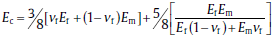

Micromechanical modeling derived from the properties of individual components of the composite and their arrangement is a very useful tool to understand and predict the composite behavior. The well-established Voigt-Reuss model[35] and Halpin-Tsai model[35,36] are used to calculate the theoretical Young's modulus of the composites.

The Voigt-Reuss model is described by:

The Halpin-Tsai model, which takes into account the aspect ratio of the reinforcing fillers, is described by:

where

The Young's modulus of the composites is plotted against the filler volume fraction in

To sum up, Nielsen's modified Kerner's equation for Young's modulus of the CSW/PVC composites is better than other models examined in this study.

The mechanical properties, especially the tensile strength, of the composites are significantly affected by the interfacial adhesion between fillers and matrix. However, it is difficult to directly measure the interfacial interaction of the matrix filled with inorganic fillers[17]. Li and Liang[15,39] proposed a new parameter, half debonding angle

σyc=σym (1-1.21sin2θνf2/3) (8)

where

The

Fig. 9. Linear dependence of 1- σyc/σym versus 1.21

This study compares the morphologies, mechanical and heat resistant properties of CSW/PVC, cPVA@CSW/PVC, Si-CSW/PVC, Ti-CSW/PVC, and SA-CSW/PVC composites. The results show that cPVA@CSW/PVC composite has the strongest interfacial adhesion between whiskers and PVC matrix, and has excellent and stable mechanical and heat resistant properties. The Young's modulus increases with increasing whisker content, resulting in an increase in the stiffness of the composites. However, the tensile strength decreases due to significant agglomeration of the whiskers at a high content. cPVA@CSW obviously improves the VST of the composites. Nielsen's modified Kerner's equation for Young's modulus is better than other models examined in this study for CSW/PVC composites. Although the half debonding angle of cPVA@CSW/PVC composite is slightly higher than that of Si-CSW/PVC composite, it has better interfacial adhesion. In general, cross-linked PVA is an effective and environmentally friendly modification method for inorganic fillers.

Acknowledgements: This research was financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (U 1507123), the Foundation from Qinghai Science and Technology Department (2014-HZ-817) and Kunlun Scholar Award Program of Qinghai Province.

The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.