Three different Cu–Zr–Co alloys, namely Cu40Zr37.5Co22.5, Cu42.5Zr45Co12.5 and Cu49Zr49Co2, were obtained by rapid cooling. The microstructure and phase formation of as-cast rods with diameters of 2 mm are compared with those of the respective ingots. An increasing Co content stabilises the B2 CuZr phase and leads to the precipitation of a ternary Cu–Zr–Co phase. The variation of the cooling rate affects the size of the B2 dendrites as well as the volume fraction and the morphology of the interdendritic phases. The mechanical properties were determined in compression and all alloys show a certain plastic deformability despite the presence of several binary and ternary intermetallic phases. The deformation mechanisms are discussed on the basis of the microstructures and the constituent phases.

Metastable alloys are characterised either by the presence of phases, which are not thermodynamically stable under ambient conditions and decompose upon thermal activation, or by microstructures on small length scales or with high defect concentrations, which tend to coarsen and anneal upon heating, respectively, or by a combination of both [1], [2] and [3]. Among other processing routes [4] and [5], metastable alloys can be synthesised using non-conventional methods, which, for instance, have intrinsically high cooling rates, such as Cu-mould casting or selective laser melting [5] and [6].

One family of metastable alloys is (bulk) metallic glasses (BMGs), or synonymously, amorphous alloys [1] and [7]. Due to their structure amorphous alloys are generally inherently brittle [8], [9] and [10] but their damage tolerance can be significantly improved when ductile crystalline phases precipitate in the glass [8], [9] and [11]. The main alloy systems, in which such composite microstructures can be formed, are based on Zr [11] and [12] and Ti [13]. More recently, also composites, which are partially vitrified and simultaneously crystallise a shape memory phase, have been developed [14], [15], [16], [17] and [18]. So far, these shape memory BMG matrix composites [19] comprise of CuZr-based [15], [16] and [17] and Cu–Ni–Ti-based [18] alloys. They stand out because of a significant tensile ductility combined with pronounced work hardening caused by a deformation-induced martensitic transformation in the crystals [15] and [19].

In the case of CuZr-based BMG matrix composites, Co appears to be an interesting alloying element. As opposed to B2 CuZr [20], B2 CoZr is stable at room temperature [21] and consequently Co additions stabilise the B2 (Cu,Co)Zr phase [22]. Even minor amounts of Co in a Cu–Zr–Al alloy seem to promote the formation of B2 crystals and to lead to a composite microstructure, which exhibits pronounced tensile strain [16]. Moreover, minor Co additions also lower the temperatures, at which the martensitic transformation occurs [23], and thus influence the shape memory behaviour of the B2 phase.

Despite the fact that metastable Cu–Zr–Co alloys might show interesting mechanical properties, to date only limited information on their phase evolution and deformation behaviour is available. Therefore, the present work is designed to shed more light on these aspects for Cu–Zr–Co alloys with an approximate Cu:Zr-ratio of one, cooled at relatively high rates. The aim is to link the different microstructures to the deformation behaviour determined under compressive loading.

Pre-alloys of Cu40Zr37.5Co22.5, Cu42.5Zr45Co12.5 and Cu49Zr49Co2 were prepared from high-purity elements (purity ≥ 99.99%) by arc-melting in a Ti-gettered Ar-atmosphere. These ingots were repeatedly re-melted to ensure chemical homogeneity. Pieces of the ingots with an approximate weight of 5–6 g were used to fabricate 70 mm long rods with a diameter of 2 mm via suction casting into a water-cooled copper mould. Additionally, samples with a diameter of 3 mm and a length of 7 mm were obtained from the ingots by means of electrical discharge machining (AgieCharmilles Robofil 230). The specimens were characterised by X-ray diffraction in transmission mode (STOE STADI P) with Mo- Kα1 radiation ( λ = 0.07093187 nm). Microstructural investigations were carried out with a Zeiss Gemini 1530 electron microscope equipped with a Bruker Xflash 4010 spectrometer to conduct energy dispersive X-ray analysis (EDX). The obtained micrographs were evaluated with the program “Leica QWin” by a line analysis to obtain the volume fractions according to the standard ASTM E 562-08. More detailed structural investigations were performed with the help of a FEI Tecnai F30 transmission electron microscope (TEM) equipped with a field emission gun. The TEM specimens were prepared by the conventional method of grinding, followed by ion-milling with liquid nitrogen cooling and a focused ion beam (FIB) treatment (Zeiss 1540 XP). Compression tests were conducted in an Instron 5869 with a constant cross head speed of 5 × 10-3 mm/s. A laser-extensometer (Fiedler) monitored the strain directly at the sample. In order to determine the yield strength the 0.2%-offset yield strength was used.

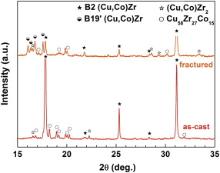

Fig. 1 displays the X-ray diffraction patterns of the ingots ( Fig. 1(a)) and the as-cast rods ( Fig. 1(b)) for the present three alloys. While the phase formation follows the binary Cu–Zr phase diagram for the alloy with the lowest Co content as shown below, the phase identification for higher Co contents becomes more difficult and obscure. It is aggravated by the fact that no ternary Cu–Co–Zr phase diagram is available and the diffraction patterns contain multiple reflections of which some are rather weak and relatively broad. Moreover, texture effects might affect the relative intensities. For this reason, SEM investigations were combined with EDX measurements in order to get a better understanding of the phase formation.

The ingot of Cu40Zr37.5Co22.5 mainly contains the B2 phase next to (Cu,Co)2Zr and an unknown phase ( Fig. 1(a)). The respective EDX measurements imply that this phase is a ternary phase with the stoichiometry of Cu58Zr27Co15. Therefore, this phase has been termed accordingly. A ternary phase with a similar composition has been recently found in Cu40.8Zr32Co27.2 [24].

When the Co content of the ingots decreases to 12.5 at.%, the reflections of the ternary phase seem to become weaker and, in addition, (Cu,Co)Zr2 reflections with a low intensity appear ( Fig. 1(a)). The main phase, however, is B2 (Cu,Co)Zr2.

The diffraction pattern of the Cu49Zr49Co2 ingot looks completely different as the main phases are (Cu,Co)Zr martensite (B19′), retained B2 (Cu,Co)Zr and (Cu,Co)10Zr7 next to (Cu,Co)Zr2. This is in good agreement with reports for a similar alloy, in which the same phases have been found [22] and [23]. Cu10Zr7 and CuZr2 are the low-temperature equilibrium phases at a composition of Cu50Zr50 [20]. They are obtained through a eutectoid decomposition of the high temperature phase B2 CuZr [20]. This B2 phase can furthermore undergo a martensitic transformation, which depends on the applied cooling rate [25]. All these phases are thus expected to form in rapidly cooled Cu49Zr49Co2.

An increase in the cooling rate only slightly affects the phase formation. For the Cu40Zr37.5Co22.5 rod with a diameter of 2 mm the reflections of the (Cu,Co)2Zr phase seem to become less pronounced ( Fig. 1(b)). Also in the Cu42.5Zr45Co12.5 rod the same phases as that in the ingot are present though the B2 reflections become weaker, indicating a decreasing volume fraction. The most distinct effect exhibits the alloy with the lowest Co content, i.e. Cu49Zr49Co2. The higher cooling rate in the rods appears to interfere with the martensitic transformation and some austenite can be retained. The B2 Bragg peaks grow at the expense of the martensite reflections ( Fig. 1(b)) because the higher cooling rate does not allow for the completion of the martensitic transformation.

The position of the B2 reflections depends on the composition and shifts to slightly smaller diffraction angles with decreasing Co content of the alloys ( Fig. 1). To explain this trend the composition of the B2 phase was measured for all three alloys by EDX and the corresponding values are listed in . The Co content in the B2 phase of Cu40Zr37.5Co22.5 is highest (about 30 at.%), decreases for Cu42.5Zr45Co12.5 and is the lowest for Cu49Zr49Co2 (about 2 at.%). Interestingly, the Co content of the B2 phase in the case of Cu42.5Zr45Co12.5 strongly depends on the cooling rate. It is about 24 at.% for the rods and only about 6 at.% for the ingot. Recent work has shown that there is a full solubility between B2 CuZr and the isomorphous B2 CoZr and that the lattice constant follows Vegard's law [26]. Since the lattice parameter of B2 CoZr is smaller than that of B2 CuZr a shift to larger diffraction angles is expected when the Co content of the B2 CuZr phase increases. This is also observed here qualitatively ( Fig. 1).

| Table 1. Crystalline phases and volume fractions determined by analysis of SEM images for the ingots and the rods of the three different compositions. The last column lists the Co content determined in the B2 dendrites via EDX in an SEM |

The present findings indicate that additions of Co increase the stability of the B2 and suppress the martensitic transformation upon cooling. Moreover, higher Co contents lead to the precipitation of the ternary phase, Cu58Zr27Co15, and of (Cu,Co)2Zr. The glass-forming ability of none of these compositions is sufficient to obtain a glassy phase in rods with a diameter of 2 mm by Cu-mould casting.

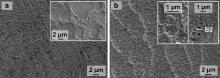

The microstructure of the Cu40Zr37.5Co22.5 rod is depicted in Fig. 2(a). The B2 dendrites have a typical size of 4–6 μm and are surrounded by multiple interdendritic phases. The B2 phase has been slightly etched away by the polishing agent so that a relief remains. As EDX measurements prove, the interdendritic region mainly consists of B2 phase and the ternary Cu58Zr27Co15 phase. Even though it is detected by X-ray diffraction, (Cu,Co)2Zr cannot be unambiguously identified via SEM in the rod. However, in the case of the ingot a substantial volume fraction of (Cu,Co)2Zr can be seen (Table 1) and this might be caused by the lower cooling rate under which the ingot solidifies resulting in larger particles. This phase forms needle-shaped particles, which are embedded in the B2 phase and the ternary phase of the interdendritic region (not shown here). The inset of Fig. 2(a) represents an SEM micrograph of the Cu40Zr37.5Co22.5 ingot, which reveals slightly larger dendrites (about 6–12 μm) due to the lower cooling rate. At the same time the volume fraction of the interdendritic phases is lower ( Fig. 2(a), Table 1) and their morphology changes. While the two phases are arranged in a plate-like or lamellar structure in the rod ( Fig. 2(a)), the B2 crystals have a more globular appearance in the case of the ingot (inset of Fig. 2(a)).

The Cu42.5Zr45Co12.5 rod ( Fig. 2(b)) also consists of B2 dendrites with a typical size of 1–5 μm and a three-phase interdendritic region. The main components of it are B2 (Cu,Co)Zr and Cu58Zr27Co15 (left inset of Fig. 2(b)). Small precipitates of (Cu,Co)Zr2 below 1 μm can be only found in the ingots but apparently the higher cooling rates prevailing in the rods avoid the formation of a significant amount of (Cu,Co)Zr2. In any case, the determination of a meaningful volume fraction is not feasible.

Also for this composition, the morphology of the interdendritic region is dependent on the applied cooling rate. In the case of the rod, the Cu58Zr27Co15 phase (brighter phase in the left inset of Fig. 2(b)) forms a continuous network in which elongated, fine, interconnected B2 particles are embedded. For the ingot, however, the interdendritic region is somewhat coarser and consists of the ternary phase in which elliptical, isolated B2 particles with the dimensions of around 200–400 nm form (see arrow in the right inset of Fig. 2(b)). Furthermore, the volume fraction of the interdendritic region is significantly higher in the rod than that in the ingot (Table1 ).

The alloy with the lowest Co content (Cu49Zr49Co2) contains dendrites as well, yet, in these, martensite laths can be detected. In between these dendrites mainly (Cu,Co)10Zr7 and some (Cu,Co)Zr2 particles are found (not shown here).

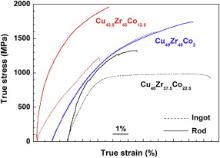

In the next step all samples were subjected to compressive loading ( Fig. 3) and the characteristic values are specified in . With the exception of Cu49Zr49Co2 there are distinct differences in the response to mechanical loading between the ingot material and the rods.

| Fig. 3. Stress–strain curves in compression for the three alloys. The dashed curves represent the ingots and the solid curves the rods. |

| Table 2. Mechanical properties of the present alloys. E, σy, σf and ɛf are the Young's modulus, yield and fracture strength and fracture strain, respectively |

The yield strength and fracture strength are higher for the Cu40Zr37.5Co22.5 rod than those for the ingot (Table 2), which could be caused in parts by the difference in the grain size (rod: 4–6 μm Fig. 1(a), ingot: 10–15 μm) and by the different volume fraction and morphology of the interdendritic phases (Table 1). The presence of (Cu,Co)2Zr in the ingot does not seem to be crucial. Instead, the larger volume fraction of the other two interdendritic phases, B2 (Cu,Co)Zr and Cu58Zr27Co15, in the rod appears to increase the yield strength. Due to casting defects like pores (not shown here) the rods tend to fail in a premature manner. The ingots, however, deform plastically up to about 8%, which is somewhat surprising if one considers the multitude of binary and ternary intermetallic phases. As will be shown below, the B2 dendrites are able to stop the catastrophic propagation of cracks and hence to increase the plastic strain. After yielding the stress increase required to continue deformation is negligible and, in other terms, the ingot does not work-harden significantly ( Fig. 3). The X-ray diffraction patterns of the fractured rods and ingots do not give any hint for a phase transformation in the B2 dendrites. Only a reduction in the peak intensities of all phases combined with a peak broadening could be observed (not shown here), which is caused by the increased amount of defects in the material [27].

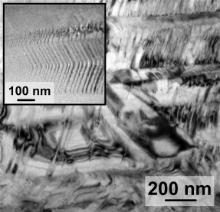

The two Cu49Zr49Co2 samples exhibit almost identical stress–strain curves, which can be expected since the phases and the respective volume fractions (Table 1) are rather similar. The slightly larger amount of B2 phase in the rods as implied by the XRD patterns ( Fig. 1(a) and (b)) might be responsible for the slightly larger plastic strain and the higher fracture stress of the rod. Both samples do not exhibit any clear yield point but constantly work-harden till fracture occurs ( Fig. 3). Also for the Cu49Zr49Co2 samples X-ray diffraction was performed after fracture and a martensitic phase transformation could be detected [22]. In addition, TEM investigations reveal an abundant formation of twins in the martensite plates after deformation ( Fig. 4).

| Fig. 4. TEM image of Cu49Zr49Co2 rod after deformation. Deformed martensite plates can be seen and within the martensite a high density of twins is present (inset). |

For the last composition, Cu42.5Zr45Co12.5, there is also a significant difference between the stress–strain curves of the rods and the ingot samples ( Fig. 3,Table 2). Especially the yield strength and the fracture stress diverge. Also in this case, the rod contains a larger volume fraction of the interdendritic phases (Table 1) and, moreover, the dendrite size is smaller (rod: 1–5 μm, ingot: 10–50 μm). This could explain the increase in the yield stress (Table 2). Both Cu42.5Zr45Co12.5 rod and ingot exhibit pronounced work hardening and as Fig. 5 reveals, a martensitic transformation takes place in the B2 dendrites of the ingot upon deformation. The B2 reflections, which are rather pronounced in the as-cast state, become weaker and broader and additional B19′ reflections occur ( Fig. 5). Surprisingly, this transformation could not be readily detected by XRD for the rods. At the same time both samples seem to fail at a relatively early stage of deformation after having reached a plastic strain of only below 5% ( Fig. 3).

In order to understand this behaviour a sample of the fractured Cu42.5Zr45Co12.5 ingot was investigated in the SEM. Fig. 6 depicts a crack, which extends over several dozens of micrometres in the interdendritic region. At lower magnifications it becomes obvious that the cracks exclusively form in the interdendritic region and form a discontinuous network, which is interrupted by the B2 dendrites. The vertical arrow in Fig. 6 marks a branch of the crack, which terminates at a B2 dendrite. This observation implies that Cu58Zr27Co15 is especially brittle and marks the path for propagating cracks. This might explain why the Cu42.5Zr45Co12.5 ingot fails at lower stresses than the respective rod despite its smaller volume fraction of interdendritic phases. The ternary phase forms a somewhat coarser network, which could facilitate crack propagation and enlarge the propensity for premature failure.

The horizontal arrows in Fig. 6 indicate martensite laths in a part of a dendrite. The martensitic transformation of the B2 phase seems to be induced by the stress concentrations in front of the propagating crack. Therefore, this material can harden significantly till fracture eventually sets in ( Fig. 3). The analysis of the fractured rod showed that a pore again caused failure.

As a final aspect, the martensitic transformation in these alloys shall be addressed in more depth. It is only detectable by XRD for the Cu42.5Zr45Co12.5 ingot and for both the Cu49Zr49Co2 ingot and rod upon deformation. This might be linked to the volume fraction of the interdendritic phases as well as to the Co content in the B2 phase. Even though it is isomorphous to B2 CuZr, B2 CoZr does not exhibit a martensitic transformation [28] and [29]. In both of the Cu42.5Zr45Co12.5 samples the Co content of the B2 dendrites is in a regime (Table 1) such that the martensitic transformation is expected to occur [22]. Though there is no direct proof of the martensitic transformation for the alloys in Ref. [22] at least the compression test curves show the typical “double yielding” indicative of a martensitic transformation [30]. Yet, the diffraction patterns imply that it only proceeds in the ingots, which have a significantly lower volume fraction of the interdendritic phase (rod: 39 ± 3 vol.%, ingot: 16 ± 2 vol.%, Table 1). Consequently the brittle interdendritic phases might act as a stiff cage and thus suppress the martensitic transformation. Neither the B2 phase of the Cu40Zr37.5Co22.5 ingot nor of the rod transforms martensitically, which could be caused by the high Co content (about 30 at.%) or again by the high volume fractions of the stiff interdendritic phases (Table 1).

The martensite in Cu49Zr49Co2 contains a substantial density of twins after fracture ( Fig. 4). It has been reported that there are two kinds of martensites in CuZr [31], of which the superstructure with the space group B33 [32] is partially twinned [33]. Most likely the material has not reached the stage, in which significant detwinning occurs [34] and [35]. The detwinning process is generally accompanied by a reduction in the strain hardening rate [34] and [35], which is indeed not seen in the stress–strain curves of the Cu49Zr49Co2 samples ( Fig. 4).

The glass-forming ability of the present Cu–Zr–Co alloys is too low in order to obtain a glassy phase in rods with a diameter of 2 mm by Cu-mould casting. Instead, all three compositions, Cu40Zr37.5Co22.5, Cu42.5Zr45Co12.5 and Cu49Zr49Co2 are fully crystalline and the phase evolution as well as the corresponding microstructures are relatively complex. An unknown ternary phase with a stoichiometry of Cu58Zr27Co15 forms at higher Co contents. This phase precipitates next to small B2 (Cu,Co)Zr particles in between the B2 dendrites and its apparent brittleness leads to its preferred cracking upon loading. The deformable B2 dendrites, however, can stop the crack propagation and hamper the formation of an extended and thus catastrophic crack. The increasing Co content in the alloys moreover reflects in the composition of the B2 dendrites and thus enhances the stability of the B2 phase and influences the martensitic transformation. At the same time the network of interdendritic phases seems to affect the martensitic transformation by shielding the B2 dendrites from the applied mechanical load. The variation of the cooling rate alters the dendrite size as well as the volume fraction and morphology of the interdendritic region and especially Cu42.5Zr45Co12.5 appears to be sensitive to the cooling rate. These microstructural changes lead to different mechanical properties and slightly different deformation mechanisms. The present study might be useful for a better understanding of the phase formation in the Cu–Zr–Co system and might help in the search of new compositions, which form bulk metallic glass matrix composites containing a shape memory phase.

References

The authors are grateful to T. Gemming, H. Wendrock, M. Stoica, S. Scudino, L. Giebeler, F.A. Javid and P. Konda Gokuldoss for stimulating discussions and S. Donath, M. Frey, H. Merker and B. Bartusch for technical assistance. P. Gargarella acknowledges the financial support by CNPq, Brazil, and DAAD, Germany.

| 1. |

|

| 2. |

|

| 3. |

|

| 4. |

|

| 5. |

|

| 6. |

|

| 7. |

|

| 8. |

|

| 9. |

|

| 10. |

|

| 11. |

|

| 12. |

|

| 13. |

|

| 14. |

|

| 15. |

|

| 16. |

|

| 17. |

|

| 18. |

|

| 19. |

|

| 20. |

|

| 21. |

|

| 22. |

|

| 23. |

|

| 24. |

|

| 25. |

|

| 26. |

|

| 27. |

|

| 28. |

|

| 29. |

|

| 30. |

|

| 31. |

|

| 32. |

|

| 33. |

|

| 34. |

|

| 35. |

|